C&C 73: SIFF 2025 Wrap-Up, Part One

The all-documentary edition

A version of this post is slated to appear at Eat Drink Films later this week. This edition includes bonus, vaguely unprofessional footnotes.

The 51st Seattle International Film Festival drew to a close on May 25, with a selection of entries available via streaming from May 26 to June 1. At this year’s fest, I paid particular attention to nonfiction titles spotlighting the troika of subjects that matter most to Eat Drink Films. Let’s begin with a libation.

Wine has its sommeliers, beer its cicerones. As the craft cocktail revolution took hold in the aughts, six authorities on spirits launched a program that would provide similar certification to bartenders. BAR (United States, 2025) tracks the 2023 class attending the Beverage Alcohol Resource 5-Day Program, held at the Culinary Institute of America’s main campus. The course consists of three days of instruction in sessions lasting up to sixteen hours, followed by two rigorous days of testing that include a written exam, a practical one (preparing half a dozen drinks in ten minutes, including one original concoction), and a blind tasting of both spirits and cocktails. Director Don Hardy’s film surveys five candidates from a broad range of backgrounds, among them a radiologist who dreams of opening his own watering hole; a woman who tends bar to finance her pursuit of a doctorate in psychology and aspires to raise awareness of mental health issues in the hospitality industry; and a young mixologist covering the cost of her participation via work/study, hustling to complete back-of-house tasks in addition to cramming. It’s easy to root for every member of this gregarious quintet, because BAR’s true subject is the openness and camaraderie of the bartending community. Dale DeGroff, one of the BAR program’s founders, notes that hospitality offers a home for individuals who don’t readily fit in elsewhere, while his colleague Steven Olson says bartending draws those who live to make people happy. Hardy also pointedly features excerpts from a panel on diversity, still a welcome and essential quality in this world. BAR is an engaging documentary, the question of who emerges from the gauntlet triumphant lending an element of suspense.1

The Chef & The Daruma (Canada, 2024) also benefits from a built-in structure. Director Mads K. Baekkevold and writer Natalie Murao frame the story of Vancouver, BC sushi maestro Hidekazu Tojo through his use of daruma dolls. Tojo explains that each of the Japanese Buddhist figurines represents a promise made to pursue a dream. Seven of these goals, among them Feed Those Around You and Share Your Passions, come into play as Tojo recounts his life. He arrived in Vancouver in 1971, making a study of what Canadians liked to eat and incorporating those ingredients in Japanese fashion. Tojo is among several chefs who claim to have invented the California roll. He presents a sturdy case, saying he developed what he initially called “the Inside Out roll” to conceal sushi elements then unfamiliar to Western diners, like seaweed. Despite the engaging daruma doll device, the documentary becomes disjointed whenever it ventures away from Tojo himself. A section on the internment of Japanese Canadians during World War II is potent but only tangentially linked to the main narrative, while a detour into the history of sake is so brief that it frustrates instead of illuminates. Tojo’s moving pilgrimage to a former salaryman’s spartan restaurant devoted to dashi, a family of broths common to Japanese cuisine, is weakened by the film’s failure to explain what dashi is. Still, Tojo makes a charismatic guide, the embodiment of his belief that “Food is a tool that can make people happy.”

Shifting to cinema about cinema, Know Her Name (Canada, 2024) is an ambitious, sprawling enterprise that plays more like a syllabus for a life-altering film studies course than a cohesive whole. Director Zainab Muse aims to tell nothing less than the story of women filmmakers and how their many contributions have been consistently neglected when not outright erased. The term “historical amnesia” is repeatedly invoked over an eighty-minute running time too short to do justice to the many topics Muse raises. Critiques of capitalism and patriarchy jockey with fleet biographical sketches of pioneering filmmakers (Alice Guy-Blaché), women who nevertheless persisted during the early Hollywood era (Dorothy Arzner and Lois Weber), and trailblazing independent artists (Esther Eng and Marion E. Wong). Muse enlists a chorus of directors including Mary Harron (American Psycho) and Deepa Mehta (the Elements trilogy) along with the generations that followed them to testify, yet issues that expressly affect them, like Harron’s cofounding of the Missing Movies initiative upon discovering that her film I Shot Andy Warhol (1996) was unavailable for streaming because of cloudy distribution rights, receive glancing treatment. Heartfelt and motivated by justifiable anger, Know Her Name is a primer on a monumental matter.

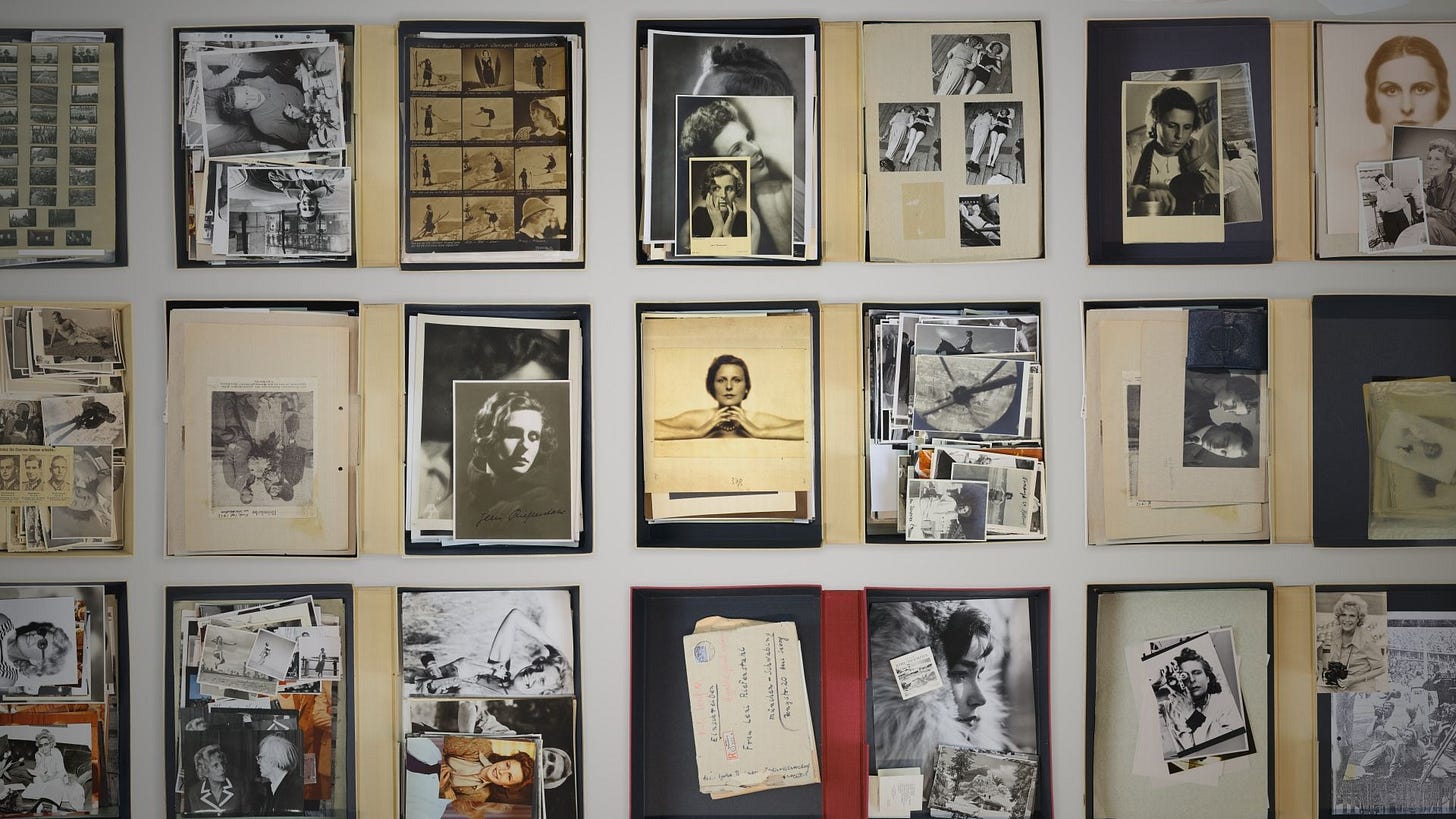

Arguably the most famous female filmmaker is the sole focus of a documentary at SIFF. Riefenstahl (Germany, 2024) is not the first movie to consider the tainted legacy of Leni Riefenstahl, whose films Triumph of the Will (1935) and Olympia (1938) served as propaganda for the Third Reich. But it is the first to make extensive use of Riefenstahl’s own archive, excavating the past that she preserved to “document 101 years of her life” and deploying it as evidence in a damning case against her. Writer/director Andres Veiel wastes no time; in Riefenstahl, the credits cast shadows. He makes canny use of individual frames of her film or still photographs: a handshake with Adolf Hitler, a warm look shared with Albert Speer, whom she regarded as a fellow artist and peer even after his prison sentence for war crimes. Riefenstahl’s festering resentment that her accomplishments are inseparable from the fascist culture they glorified registers strongly; she would spend decades of those 101 years shifting goalposts and mounting legalistic arguments to excuse herself. The film includes incredible footage of a 1970s German talk show appearance Riefenstahl made alongside a woman of the same age who resisted the Nazis. The look of muted fury on Riefenstahl’s face when her fellow guest accuses her of making “Pied Piper films” is terrifying. Riefenstahl logged every response that appearance received, recording each supportive telephone call and filing dissenting opinions under the telling category of “Those with different views, Communists, Jews, etc.” Veiel also finds a wealth of material in outtakes from Ray Müller’s justly acclaimed The Wonderful, Horrible Life of Leni Riefenstahl (1993). The earlier documentary was long regarded as definitive, but Veiel unearths clips of Riefenstahl engaged in diva-level badgering, haranguing Müller about what subjects he can raise and how he can phrase questions. Veiel’s film occasionally overreaches, as when it weakly contends that a misunderstanding of Riefenstahl’s direction during a brief stint as a “war correspondent” in 1939 may have directly led to the deaths of almost two dozen Jewish prisoners in Poland. But overall, Veiel rebuts his subject’s claims with relentless precision. He counters her insistence that the Roma children she took from Nazi camps to cast as extras in her final narrative feature Lowlands (shot during WWII, released in 1954) all survived the war when in fact most of them were killed at Auschwitz, and shows her lying about the manner in which she chronicled the lives of the Nuba tribespeople of Sudan, photographic images which now feel opportunistic. Veiel’s exploration of how one person’s unshakeable conviction in their version of the truth, including their own victimhood, can distort the record feels newly and glaringly relevant.2

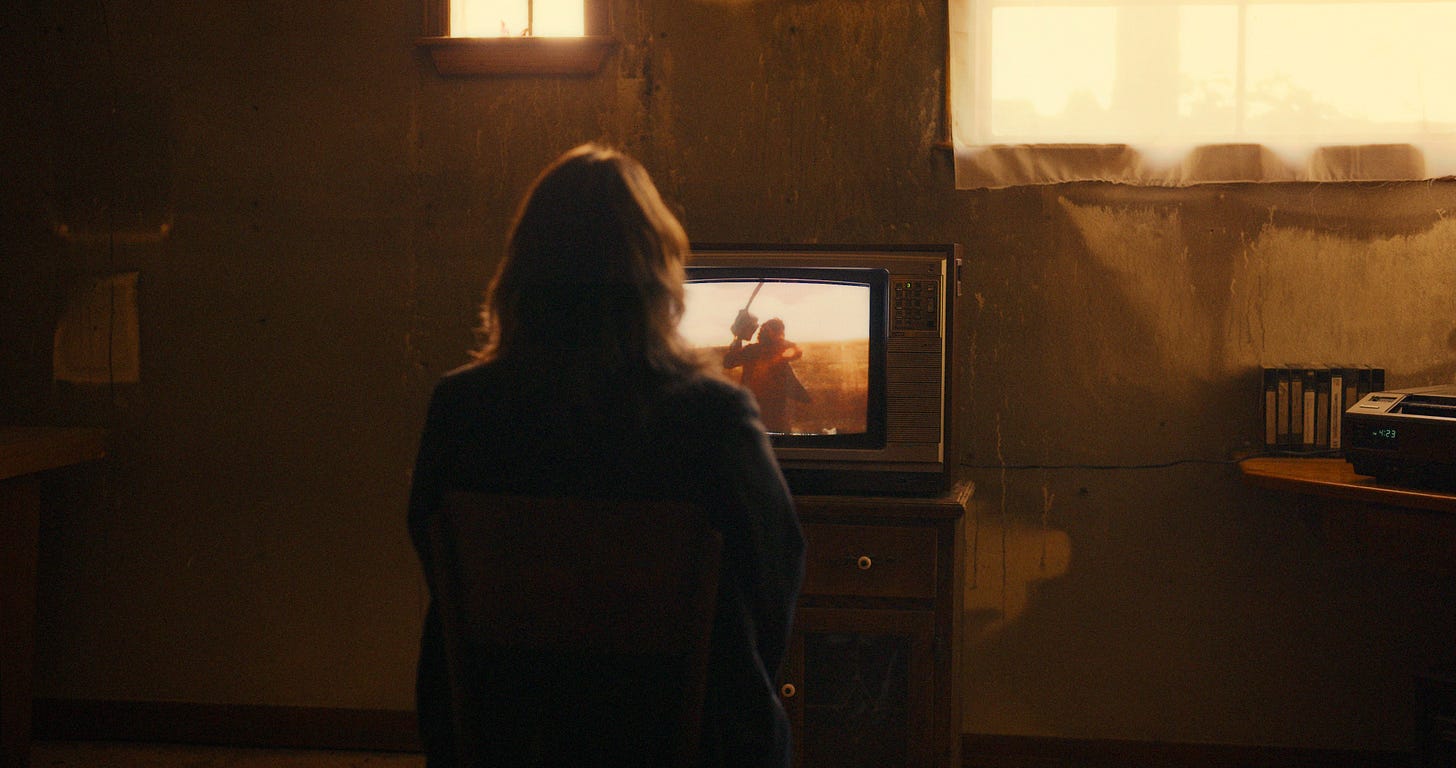

Alexandre O. Philippe, a specialist in films about films, has already made documentaries about Psycho (1960) and Alien (1979), among others. In Chain Reactions (United States, 2024), he turns his attention to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), described as a “grindhouse American masterpiece” by one of his interview subjects, filmmaker Karyn Kusama (Jennifer’s Body, Destroyer). The m-word is not used lightly; by the end of Chain Reactions, admirers of the horror classic directed and cowritten by Tobe Hooper have compared it to the work of Ingmar Bergman, Stan Brakhage, and Andrei Tarkovsky—and what’s more, you understand why. (Hooper’s cowriter Kim Henkel is an executive producer of the documentary.) In five separate chapters, Philippe allows a prominent TCM fan to expound on the hold Hooper’s film has over them. No one who has read Silver Screen Fiend: Learning About Life from an Addiction to Film (2015) will be surprised by the incisive criticism from actor/comedian Patton Oswalt. He singles out the unnerving sense that “the killers in the movie have stolen a camera and they’re filming all this,” calls the “porch scene” when one of the teenaged victims almost escapes from Gunnar Hansen’s Leatherface a dividing line for horror film fans, and offers a genuinely disturbing theory about the root of the madness propelling the action. Auteur Takashi Miike (Audition, Ichi the Killer) only saw the movie, known as The Devil’s Sacrifice in Japan, because he couldn’t get into a sold-out revival of Charlie Chaplin’s City Lights (1931), and speculates on the course his life might have taken otherwise. The yellowed, “terribly shitty” VHS prints of TCM available in Australia allow critic Alexandra Heller-Nicholas to consider it an American cousin to Aussie films like Wake in Fright (1971). Surprisingly, Stephen King’s segment proves the lightest on insight, although he does say that good horror is “supposed to go too far.” Kusama rounds out the company by discussing Hooper’s opus as an explicitly political work, considering Leatherface and his clan as displaced workers and describing the harrowing family dinner scene as the “saddest, scariest depiction of broken masculinity.” All five analysts acknowledge the unexpected beauty in Hooper’s film and their compassion for the characters typically viewed as the villains; as Heller-Nicholas puts it, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is a “home invasion” film when viewed from Leatherface’s perspective. Fifty years and multiple iterations later, Hooper’s independent original remains a landmark and an unlikely source of empathy.

BAR and Know Her Name are among the thirty films streaming as part of the Seattle International Film Festival through June 1. Here’s part two of my SIFF 2025 coverage.

One of the pleasant surprises of BAR was seeing people I know in the film, chief among them my friend Anu Apte. The owner of Seattle’s Rob Roy and several other fine establishments, Anu is a graduate of the BAR program and she’s now a member of the faculty.

The plot of the second Lillian Frost and Edith Head mystery by my half-alter ego Renee Patrick, Dangerous to Know, touches on a real-life 1938 screening of Olympia in Los Angeles, with Riefenstahl appearing as a character in the book.