C&C 72: The Search for Inspirado

My stint as an Edgars judge and some vintage reads get me back in the fiction groove

The Edgar Awards, given out by the Mystery Writers of America, were held in New York City on May 1. This year’s ceremony will likely be remembered for the own goal of kicking off the proceedings with a clumsy video featuring AI-generated versions of Humphrey Bogart and the award’s namesake Edgar Allan Poe. The bit by all accounts died on its ass in the room, was deemed “creepy” by Publishers Weekly, and prompted MWA’s board to issue an apology. Scott Frank, who won the Best Television Episode Teleplay award for Monsieur Spade,1 rightly called it out as a presentation on how AI would steal writers’ jobs. I missed Bogie on the live feed that night, but Poe and his cat left me suitably appalled.

I tuned in out of a sense of ownership, because I served on the jury for Best Juvenile Mystery. I surprised myself by agreeing to do it; I’d just wrapped up a stint as a judge for a different literary competition in 2023, one that left a bad taste in my mouth because of administrative decisions made by the organizers. But the pitch from Kate Hannigan, chair of the Best Juvenile jury, was persuasive, and I thought it would be a refreshing change of pace to spend a year with books meant for readers ages 5-12. Kate’s organizational prowess simplified the process, our fellow jurors—Deborah Atkinson, Kathleen Kalb, and Taryn Souders—were delightful, and our deliberations were lively without an ounce of acrimony.

What blew me away was the overwhelming quality of the titles under consideration. I would have loved many of these books when I was a kid, with several of them ranking among my favorite reads of 2024.

I was also struck by the purity of these efforts. Writing is a brutal business. Nobody should go into it expecting to get rich. Still, the thought always lurks at the back of your mind: maybe my book will break out. Even YA authors aren’t immune; that demographic has spawned many a successful franchise. But when you write for the youngest readers, you know going in that your book won’t be chosen by Reese or Jenna for their book clubs. You tell these stories because you believe they matter, the greatest possible reward being that you help spark a child’s lifelong love of literature.

Immersing myself in children’s books for a year was a much-needed balm. I realized as my reading began that I haven’t written a word of fiction since the most recent Renee Patrick novel, Idle Gossip (2022). I’ve been busy with screenwriting and nonfiction projects, several involving terrific collaborators. There are novels I want to write. But owing to that hectic schedule and, I must admit, disillusionment with publishing, fiction stopped being a priority.2 Still, as a wise man told me, writing and publishing are separate enterprises that only occasionally overlap. I didn’t want my rude awakening to keep me from the work that’s important to me, and I longed for a solo project not beholden to any timetable. Diving into books not aimed at me helped get me back on that horse.

My Edgar duties completed, I sought inspiration elsewhere. Nothing motivates like exposure to great work, so I gave myself a side quest. I would finally read the novels behind several classic big-screen thrillers I’d seen multiple times, then watch the movies again. Let’s take them in chronological order.

The 1962 film adaptation of The Manchurian Candidate, directed by John Frankenheimer, features one of my all-time favorite performances. As Raymond Shaw, Laurence Harvey manages to be completely believable as an isolated, fundamentally unlovable man while simultaneously making your heart ache for him. That cruel conception of the character starts with Richard Condon’s 1959 novel: “The shell of armor that encased Raymond, by the horrid tracery of its design, presented him as one of the least likeable men of his century.”

The novel and film popularized the post-war boogeyman of brainwashing, the title now part of the language. Condon occasionally falls prey to a fussy, ornate style.

The sergeant’s account of his past was ancient in its form and confusingly dramatic, as perhaps would have been a game of three-level chess between Richard Burbage and Sacha Guitry.

Um, OK.

At other times, Condon can be incisive—“no matter how much they would like the world to think so, the planet is not populated entirely by businessmen no matter how banal the quality of conversation everywhere has become”—and brutal about matters of great import.

The other members of Marco’s I&R patrol whose minds believed in so many things that had never happened, although in that instance they were hardly unique, returned to their homes, left them, found jobs and left them until, at last, they achieved an understanding of their essential desperation and made peace with it, to settle down into making and acknowledging the need for the automatic motions that were called living.

I missed the depth of the book’s friendship, tenuous and essential, between Raymond and his former CO Bennett Marco, played in the film by Frank Sinatra. Raymond’s mother Eleanor, immortalized by Angela Lansbury, is even more formidable on the page. George Axelrod, in adapting the novel, wisely trimmed the incest out of the plot. Reading the book in 2025 is an eye-opening experience.

… it was consistent with one of Raymond’s mother’s basic verities, that thinking made Americans’ heads hurt and therefore was to be avoided.

As she had anticipated he would, Johnny Iselin had agreed with everything she said, which, when boiled down, expressed the conviction that the Republic was a humbug, the electorate rabble, and anyone strong who knew how to maneuver could have all the power and glory that the richest and most naive democracy in the world could bestow.

Not revisiting: the 2004 adaptation directed by Jonathan Demme. It’s well-cast—Liev Schreiber is up to the unenviable task of succeeding Laurence Harvey, with Meryl Streep as Eleanor and Denzel Washington as Marco—but shorn of any political context, the villain being Hollywood’s standard-issue evil corporation.

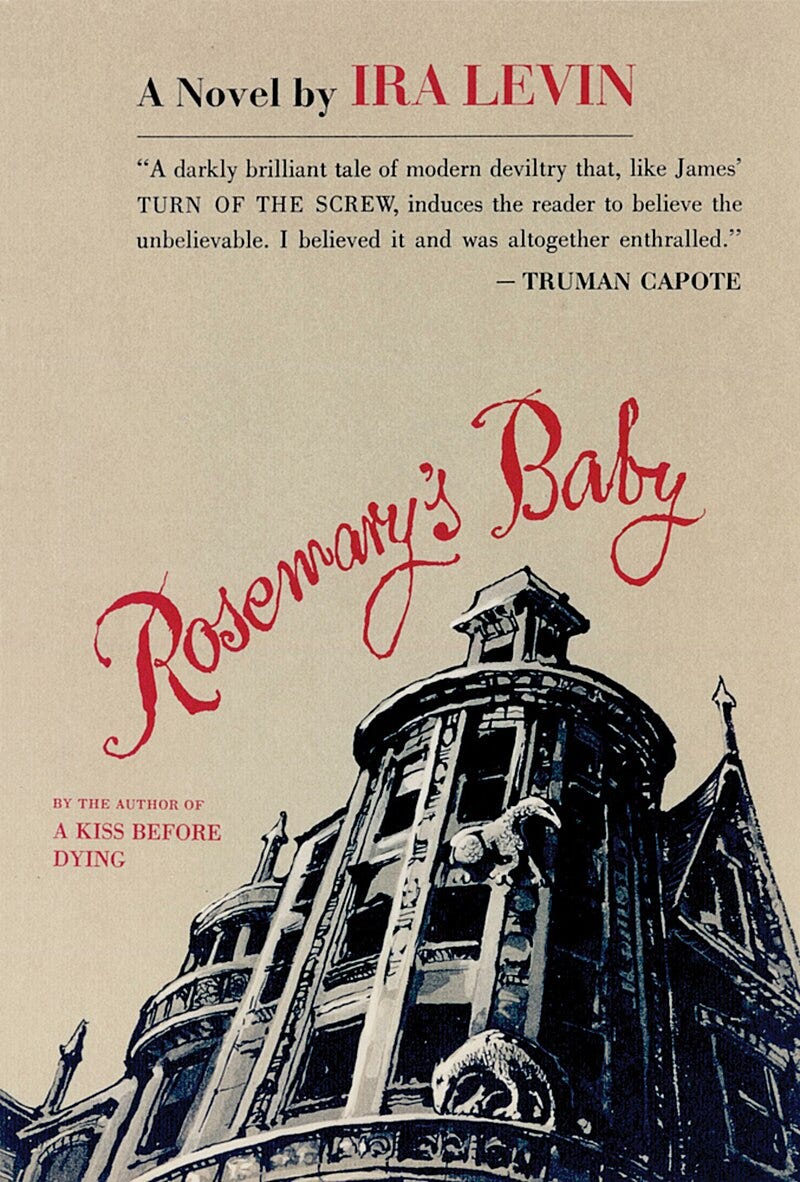

This next one embarrasses me. I could have sworn I’d read Rosemary’s Baby (1967) by Ira Levin years ago but apparently I did not, given the force with which the book hit me. Credit Levin’s eminently rational prose style, befitting the harrowing tale of a woman desperate to convince herself in the face of overwhelming evidence that everything is fine—and that if there is a problem, it’s most likely her. Roman Polanski was scrupulously faithful in his adaptation, allegedly asking Levin if he could see the specific shirt ad in the New Yorker mentioned in the book. There’s only one noteworthy excision in Polanski’s script, an extended sequence when, early in her pregnancy, Rosemary Woodhouse spends a weekend alone in the country to consider the coming changes in her life. It’s an entirely internal passage that deepens our understanding of and identification with Rosemary but isn’t missed onscreen.

As for the 1968 film, it’s the rare one that is always even better than you remember. 10/10, no notes. John Cassavetes, playing one of the most loathsome characters in movie history, serves up a hilarious portrait of actorly self-absorption. Additional points for the genius of casting Ralph Bellamy, famous for playing the spurned party in screwball comedies, as a sinister obstetrician.

Not bothering with: Levin’s own ill-advised sequel Son of Rosemary (1997); the 1976 TV movie Look What’s Happened to Rosemary’s Baby, which at least brought back Ruth Gordon to reprise her Oscar-winning turn as Minnie Castevet; the 2014 miniseries directed by Agnieszka Holland and starring Zoe Saldaña as Rosemary; the nesting-doll prequel Apartment 7A (2024), with Julia Garner and the estimable Dianne Wiest taking on Gordon’s role.

Marathon Man is the exception here in that I’ve never liked the 1976 movie. The plot doesn’t hang together, and Dustin Hoffman, pushing forty, is never remotely believable as a grad student.3 Imagine my surprise to read William Goldman’s 1974 novel and love it. The plot still doesn’t make a hell of a lot of sense—in the introduction to the reissue, Goldman admits to aspiring to the level of Graham Greene, but what he’s written is a sterling example of what’s too frequently dismissed as an “airport novel”—and it doesn’t matter, given Goldman’s engaging voice. Like Rosemary’s Baby, Marathon Man is not only a New York novel but one of specific neighborhoods. I fell hard for it during the sublime opening scene in Yorkville, in which two alta cockers replay World War II by jousting on the city streets, Goldman flitting effortlessly between multiple perspectives. It helps to be a sports fan; the “marathon man” conceit of the title, Babe Levy’s dedication to long-distance running and his admiration of athletes like Paavo Nurmi and Abebe Bikila, is woven into the text, and Goldman convinces us of a hired killer’s skill by comparing him to Walt Frazier of the Knicks. And again, there are the lines that, read today, bring you up short.

Defending was always so hard. How great life must be if all you ever did was attack. Wouldn’t it be terrific to wake up one morning and find yourself Attila the Hun?

As for the movie, I still don’t like it. Hoffman will always be too old. I watch it for the infamous dentist scene and Roy Scheider. There aren’t enough Roy Scheider movies.

Still on the fence about: Brothers (1986), Goldman’s sequel, in which he resurrects a character from the dead in service of a preposterous-sounding plot. But it’s Goldman, so never say never.

At any rate, all the inspiration seems to have turned the trick. After a four-year layoff, I’m finally outlining a new novel of my own.

And yes, the title of this newsletter is a Tenacious D reference, thanks for noticing. Could you—one time—kick it, what the fuck?4

A very good show that more people should have watched

I should explain that while Rosemarie and I are not by any means finished with Renee Patrick, she is on indefinite hiatus for the moment, although I have been working on a Renee Patrick-related project that I am not at liberty to discuss.

My dream adaptation would star a Social Network-era Jesse Eisenberg as “Babe” Levy. He’d bring the perfect blend of intelligence, prickliness, and lank physicality.

I rewatched the episode prepared for baby-faced Jack Black, but I was not ready for a clean-shaven Paul F. Tompkins as the open mic host.

I judged the Juvenile category last year and was surprised by the number of truly fantastic books, although it became a bit overwhelming when 80 books arrived on my doorstep. I enjoyed The Manchurian Candidate when I had the chance to see it years ago. I also had no desire to see the remake. I still regret seeing the remake of Psycho with Vince Vaughn.

This was great, VK! Loved the book vs film commentary, just like NC Magazine. You really nailed it about Marathon Man the movie.