C&C 70: Dune It Again

Revisiting David Lynch’s least-loved movie to remember why it matters to me

When David Lynch died in January of this year, several Seattle film organizations announced plans to pay tribute to his life and career. It made the passing of one of the great cinematic artists both easier to take and harder to bear; seeing his work in a theater with an audience, as it was meant to be experienced, would also serve as a reminder that we will never get more of it.

I was thrilled when SIFF revealed that its salute would include a 4K version of Dune (1984) on the massive SIFF Downtown screen. Lynch’s adaptation of the Frank Herbert science fiction novel is his great misbegotten movie. A critical and commercial catastrophe, it has been superseded by Denis Villeneuve’s acclaimed two-part (2021/2024) treatment of the book, and even by Alejandro Jodorowsky’s aborted attempt to wrangle the material in the 1970s, chronicled in the 2013 documentary Jodorowsky’s Dune. Whatever positive feelings exist toward Lynch’s version stem from the fact that his deal with producer Dino De Laurentiis included a provision that brought his next masterpiece Blue Velvet (1986) into being.

Unless you ask me, that is. I’ll admit it without qualification. I love David Lynch’s Dune. I loved it in 1984, and having revisited it, I love it now.

Part of that is timing. It was the first Lynch movie I saw, and I was an impressionable kid at the time. I’d read the book and was there on opening day. I became obsessed with it, watching it repeatedly on cable. It’s safe to say that I’ve seen Lynch’s Dune more times than all the Star Wars movies put together.1 I even watched the (lousy) expanded television version from 1988 that Lynch disavowed, opting for the Alan Smithee directorial credit and blaming the script on Judas Booth, presumably Frank Booth’s brother.

I’m a fan of the Villeneuve films. But his version of the desert planet Arrakis has always seemed too clean, like a high-end spa. You could set the next season of The White Lotus there. Lynch’s entire Dune universe, by contrast, is grimy and weird from the get-go. After not one but two turgid, studio-mandated introductions, the film opens with the emperor of the known universe (Jose Ferrer) being told what’s what by a member of the Spacing Guild. All the machinations that follow are about keeping the spice, the psychotropic substance harvested on Arrakis that makes interstellar travel possible, flowing. Lynch puts that front and center by showing us the consequences of exposure. The navigator we encounter at the start of the movie has mutated, its distended body floating in an ornate tank of spice gas. You look at this creature and think, That motherfucker can fold space.2 By the time this bizarre initial scene is over, you accept that the many plots within plots are worth it to control the spice.3

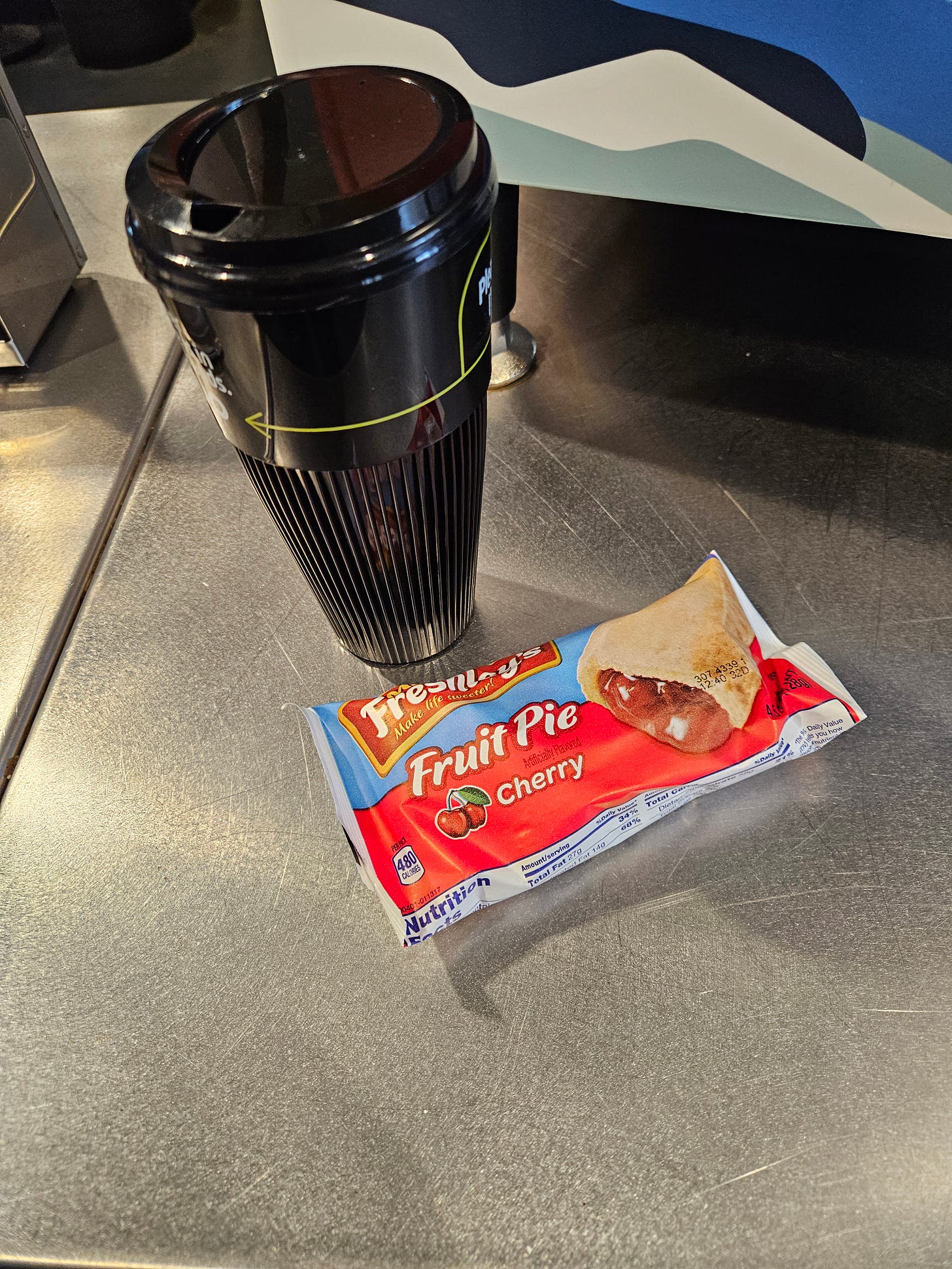

I couldn’t remember the last time I watched Dune all the way through, and I hadn’t seen it on the big screen since 1985. Forty years was long enough. SIFF ran a special, serving black coffee and cherry pies, and I wasn’t about to pass up the opportunity to pay my respects to Twin Peaks.

The movie still works for me, all of it, the good parts and the bad. The clunky technology and the clunkier exposition. The battle pugs and the milked cats. Sting in his underwear from the Albert Speer collection. The Toto guitar twang that kicks in when Paul Atreides (Kyle MacLachlan) surfs on a sandworm for the first time. The same sequence in Villeneuve’s Dune: Part Two is genuinely breathtaking, a visionary piece of filmmaking. You know what would make it more epic? Guitar twang. It was fascinating to return to Dune after seeing Lynch’s other films and appreciate it as a true David Lynch movie, reliant on visions and dreams, drawing power from repetition. Some shots of Giedi Prime, home world of the evil Harkonnens, prefigure images that appear in Twin Peaks: The Return. Dune is not Lynch’s best movie. But it’s the one that will always mean the most to me. In December I reviewed Chris Nashawaty’s The Future Was Now, about the science-fiction summer of 1982. But 1984, the year of Dune and The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the Eighth Dimension, was likely the one that shaped me.

SIFF alternated Dune with Wild at Heart (1990), a Palme d’Or winner and the one Lynch film I’m in no hurry to revisit. It left me cold when I saw it on its original release. I wonder if that’s because the Barry Gifford novel on which it’s based already feels like a Lynch movie. When the source material is deep in a filmmaker’s wheelhouse, the result can sometimes feel like, as they say in comedy, putting a hat on a hat. I place the Coen Brothers’ No Country for Old Men (2007) in that category, and yes, I know Joel and Ethan’s adaptation of Cormac McCarthy’s novel is their most acclaimed film, thank you. But sometimes putting a hat on a hat succeeds. Alfred Hitchcock lost the rights to She Who Was No More (1952) by Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac to Henri-Georges Clouzot, who transformed the book into Diabolique (1955). Legend has it that Boileau-Narcejac deliberately set out to write a novel containing Hitch’s favored obsessions and themes. The Living and the Dead (1954) became Vertigo (1958), with Hitchcock confronting his fixations head on and yielding his most personal work.

What I’m Drinking

Odds are I would not be married if it weren’t for David Lynch. I met Rosemarie at an advertising company where she was vice president and I was the lowest-ranked employee; the office printers were more important than me. She was, and remains, out of my league. But Twin Peaks had just debuted, and when I spied the photos of Agent Cooper (MacLachlan) and Josie Packard (Joan Chen) hanging in her office, I had a way in. We’ve been together ever since.

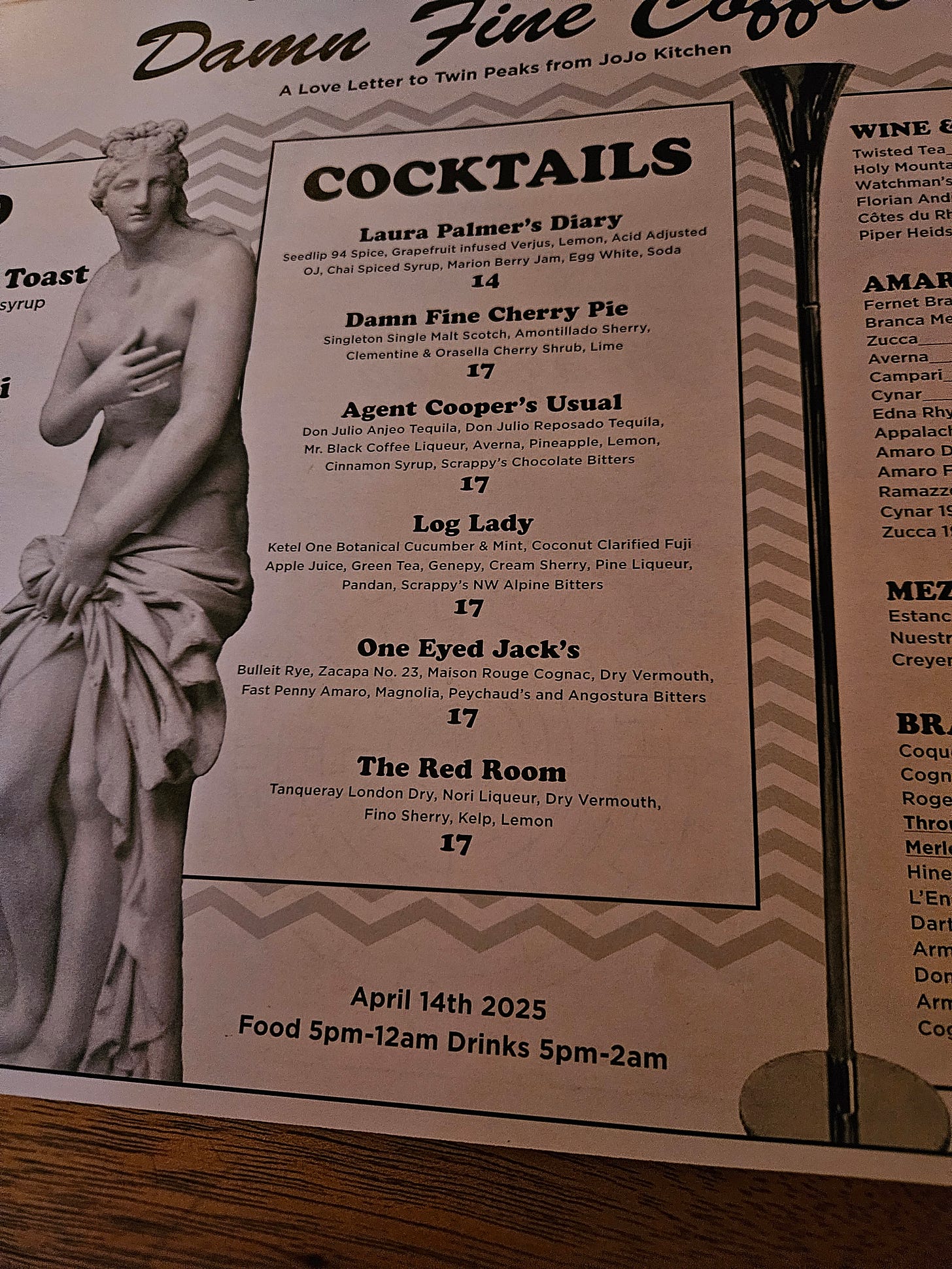

When my friend Matt Pachmayr and his cronies at No Call No Show announced a Twin Peaks pop-up, I put it on my calendar. The cocktails came courtesy of JoJo Kitchen, bar manager at Rob Roy and a huge Peaks fan, and she outdid herself with this menu, which spotlights Pacific Northwest ingredients.

I enjoyed the One-Eyed Jack’s, a variation on the Vieux Carré, and the Damn Fine Cherry Pie. I didn’t sample the Log Lady, but the vessel in which it was served cannot be faulted.

What I’m Reading

I’m also fairly sure Rosemarie and I wouldn’t be married if there hadn’t been a Pizza Hut across from our office. A waitress straight out of Hell or High Water (2016) worked there, routinely giving her customers a hard time. When I started bringing Rosemarie there for lunch once a week, the waitress sensed something was up and brought her A game, laying into me so I could banter back. If Rosemarie and I hadn’t eloped, we’d have invited her to the wedding.

I thought of that Pizza Hut when I read Meghan McCarron’s fascinating and ultimately sad New York Times story on the decline of the American middle-class restaurant. I was out with a friend recently when a bartender said that her comfort food was a recreation of the Olive Garden salad, down to the huge unsliced olives. That prompted a long conversation about dining out at chain restaurants back in the day, when going to Red Lobster meant something. The article also reminded me that I will never comprehend millenials’ fetish for authenticity.

Speaking of generations, nope, no reason why I’m linking to Steven Kurutz’s Times feature on Gen X-ers freaking out about their careers. No reason at all. Unless it’s to remind you that Flipside by Chris Wilcha, a documentary highlighted in the piece, is my favorite film of 2024. Related: Sara Kaye’s You Should Hire a GenX-er with an Art Degree Before It’s Too Late.

I loved Amanda Petrusich’s interview with Jeff Bridges for The New Yorker, prompted by Bridges’s new album of songs recorded in 1977-78 but touching on life and creativity. I need to heed the Dude’s counsel when he talks about the human need to get out of your own way.

How do you put yourself in that position? How do we create instances that call on us to do what you’re talking about? To get out of the way? I consider myself a very lazy person. But then I say, “Look at all the stuff that you’ve done, man.” But I’m just—I’m so . . . I’m so lazy. [Laughs.] The high in life, for me, is intimacy. I’ve been married for forty-eight years. We’ve known each other for fifty years. And it gets better and richer and all of that. Then there’s intimacy with yourself, where you don’t get too mad at yourself for being lazy. [Laughs.]

What I’m Watching

Good luck sitting still during We Want the Funk! (2025), the documentary directed by Stanley Nelson and Nicole London. Part of PBS’s Independent Lens series, it’s informative, inclusive, and irresistible. It’s also exactly the kind of film less likely to get funded now, so you might as well enjoy it while we have it.

Not that big a boast. Sure, there are plenty of Star Wars movies, but I’ve only seen four of them. That’s a comment on my taste, not the franchise. The first physical altercation I ever got into was in Catholic school, when I said I liked Close Encounters of the Third Kind more than Star Wars. I started down this road early.

I’ve always thought that Lynch, a devoted practitioner of Transcendental Meditation, would be drawn to the concept of “travel without moving.”

Echoing down the halls at early ‘80s Universal: “Yep, gonna be bigger than Star Wars!”

“You know what would make it more epic? Guitar twang.” Vince Keenan, deadly serious comedic critic, poet of 1984 and Pizza Hut. This essay made my day. Thank you Vince!

A notably GREAT post from Vince Keenan (someone who already has such a high bar)