C&C 48: Blue Notes and Green Fears

Two new books on jazz, or why melody matters in non-fiction as much as music, plus a round for the house

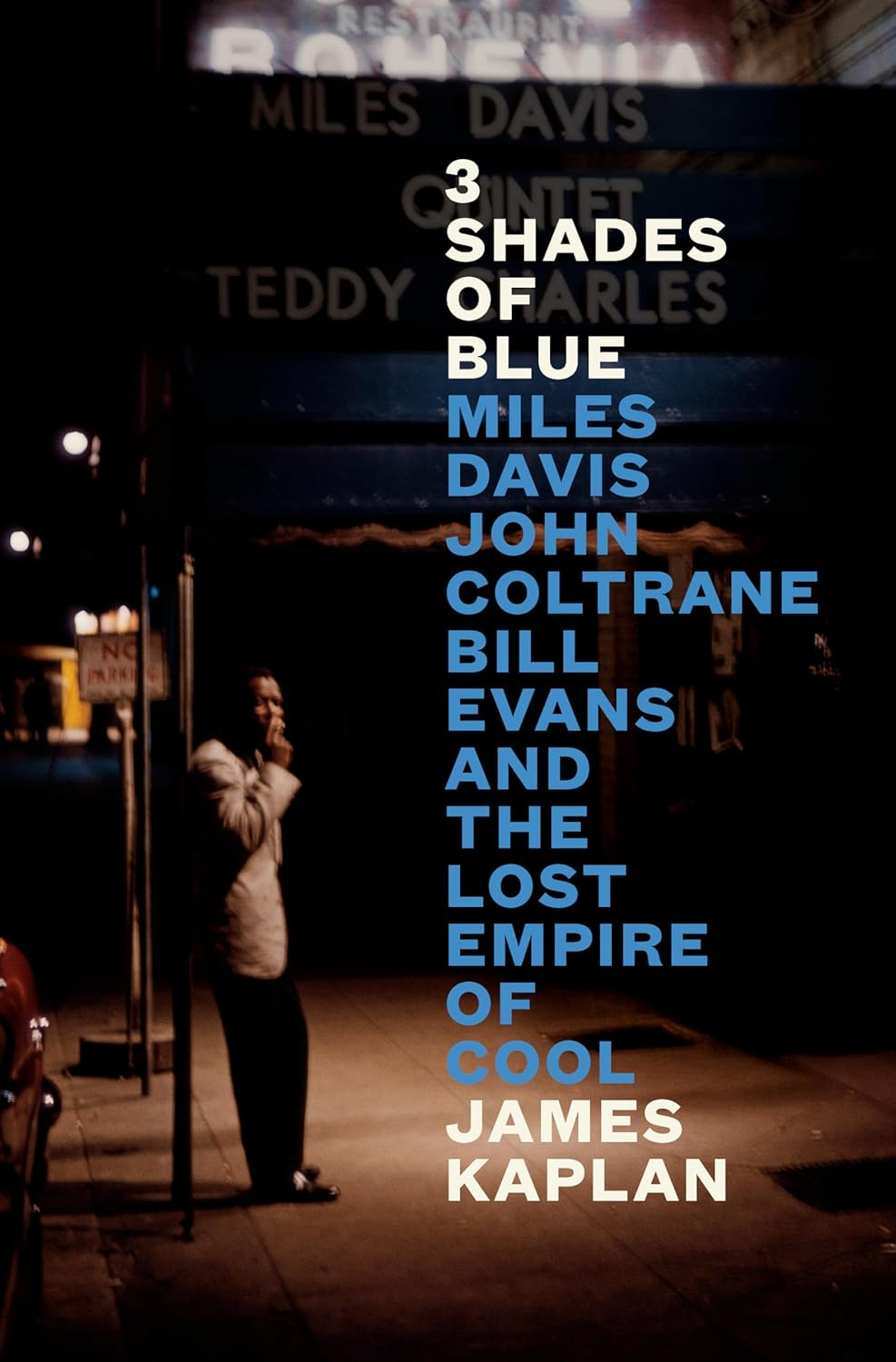

In 3 Shades of Blue: Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Bill Evans, and the Lost Empire of Cool (2024), James Kaplan closes the introduction, or as he styles it, the prelude, with a thesis statement so straightforward it would gladden the hearts of English teachers everywhere. “This is the story of the three geniuses who joined forces to create one of the great classics in Western music,” he writes, speaking of “what would become the bestselling, and arguably most beloved, jazz album of all time, Miles’s Kind of Blue,” released in 1959.

The sentence gives us a distinct destination, the two recording sessions featuring the subtitle trio along with Cannonball Adderley, Paul Chambers, and Jimmy Cobb, with pianist Wynton Kelly sitting in for Evans on one track. That fixed point on the horizon not only allows for orientation but also permits a more digressive journey, full of day trips and detours. Kaplan knows such flexibility will be necessary, because his true focus is that lost empire of cool, the diminution of jazz’s cultural cachet. Davis’s album is presented as an apotheosis: an unparalleled height from which the artform could only fall.

Writing the biography of a record involves more than weaving together the lives of some of the artists who played on it. Kaplan, perhaps inspired by the virtuosity of his subjects, engages in some structural bravado of his own with a lengthy closing chapter running almost a quarter of the text, recounting the impact of Kind of Blue, which “was like a stone tossed into a dark lake, the concentric waves of its power radiating smoothly, silently, in all directions.” The before-and-after approach means that names like Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, and Ornette Coleman become part of the story. A recurring theme is jazz’s rich tradition of tutelage, as established performers select up-and-coming collaborators who seem like counterintuitive choices only to unlock something in themselves and their mentors (Parker anointing Davis, who in turn tapped Coltrane and others).

Another refrain is the destruction wrought by drugs on the jazz world. Parker’s “occasional ability to play his best while high … in its own dark way, was like John Henry or Paul Bunyan: a classic American folktale, with Bird as the superhuman hero.” Drug use becomes something of a badge of honor among people who viewed themselves as outsiders, Kaplan positing that many musicians enjoyed “not just heroin itself but everything about it: talking about it in a special, coded language; obtaining it, administering it.” Bill Evans would be literally crippled by his addiction, changing what and how he played before his death.

But as we barrel toward those twin dates at Columbia’s Thirtieth Street Studio, Kaplan returns again and again to the broader transformations in jazz. As he notes, “bebop had limited communicative powers: there weren’t many bebop tunes you could hum or whistle. It was a private language, for adepts to play and enthusiasts to feel in on.” It “demands a lot of the listener; ultimately, in many ways, it is musicians’ music.” Jazz would go “from a music that brought the country together” to maintaining “a small but real place in the American culture at large” in the late 1950s until it finally becomes “a niche music, one that fewer and fewer people found understandable or compelling.” That’s a sprawling, cantankerous, even divisive narrative, and only Kaplan’s artful framing allows him to attempt telling it.

It nearly didn’t happen. In the acknowledgments, Kaplan describes the project he initially pitched to publishers, which would track the lives of four prominent Americans—James Dean, Albert Einstein, Charlie Parker, and Wallace Stevens—who all happened to die in 1955. Trouble was, that fact was the only connective tissue between them. An editor who passed on the idea then suggested a triptych of Davis, Coltrane, and Evans.

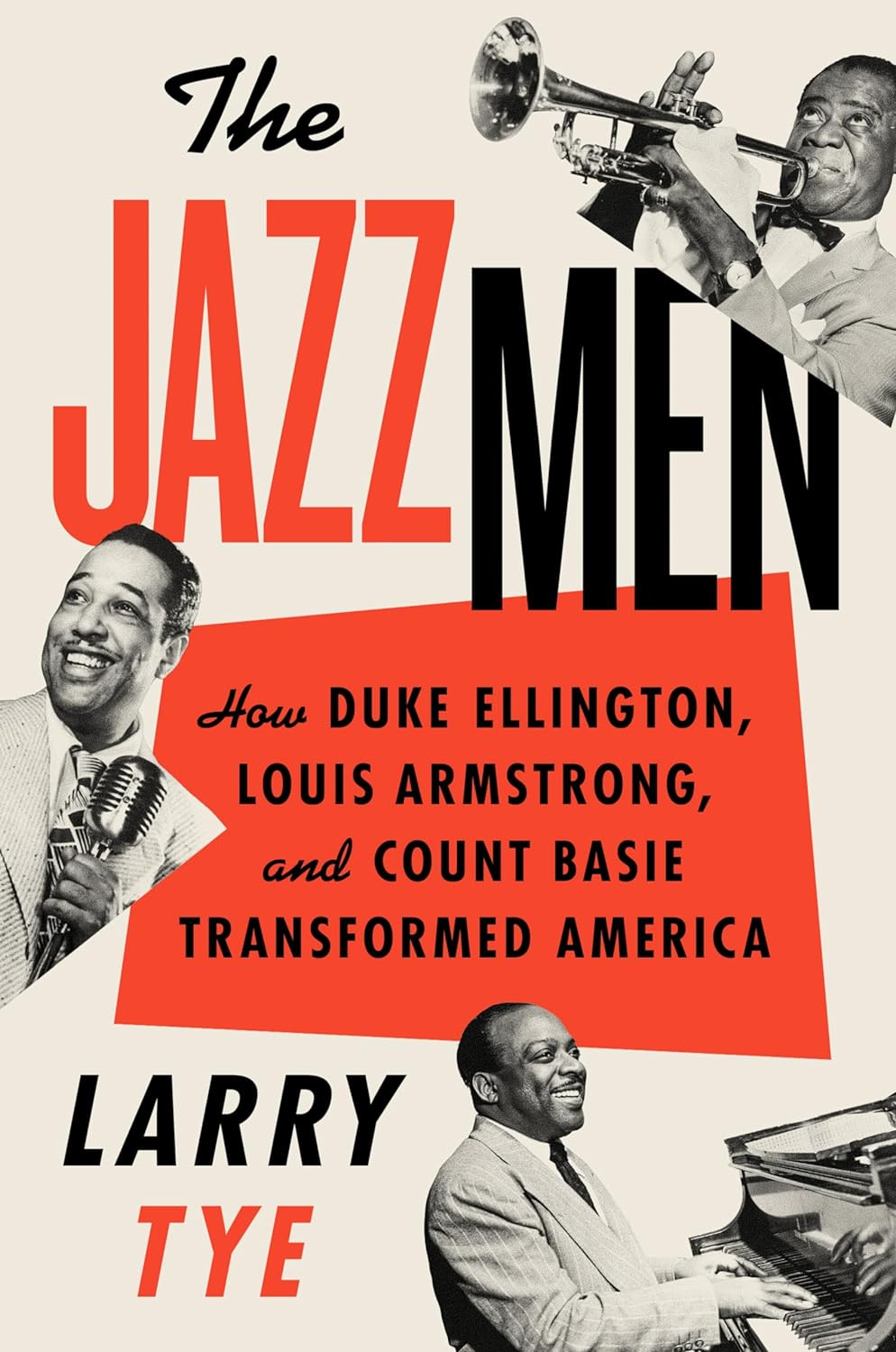

Another recently published joint biography stumbles into the pitfall that Kaplan narrowly avoided, which is ironic given that jazz should be fertile ground for an approach based on finding unexpected harmonies. Larry Tye’s The Jazzmen: How Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, and Count Basie Transformed America (2024) considers these legends in concert despite the fact that they never performed together in concert. Tye asks us to imagine such a collaboration as he repeatedly states that while these titans admired each other, their interactions were limited. A collective appraisal should illuminate truths that might otherwise have gone unnoticed, but Tye never mounts a convincing argument for studying the trio in unison outside the obvious links of race, age, and profession. He routinely tosses in strained comparisons. Duke is Shakespeare, Satchmo is Twain, and Basie is a musical everyman. Ellington represents the future as Armstrong appealed to nostalgia, while the Count makes music anyone can understand. (As those examples suggest, Basie, the least lionized of the group, comes in third again here.) Unlike Kaplan, Tye hasn’t given himself a strong melody to which he can return, granting shape to his improvisations. He has certainly done the research, and there are strong sections like his repeated engagement with the issue of how Armstrong was perceived by Black audiences and entertainers as civil rights moved to the fore—he doggedly kept the problematic “Sleepy Time Down South” in his repertoire for decades—and the passages on Ellington’s relationship with Billy Strayhorn and his interest in more esoteric music later in his career. But overall the book moves diligently along a checklist of topics like women, gangsters, and money, using each as a prism through which to view each man in turn. A chapter entitled “Toilet Truths, Food Fetishes, and Other Medical Matters” will answer any questions you may have had about Louis’s love of laxatives or why Ellington feared anything green. The Jazzmen knows all the notes, but it never swings.

I was hesitant about this piece, enduring multiple false starts. I feel reasonably comfortable discussing the writing of these books, but not necessarily their respective takes on the music. Jazz is what I listen to the most, but I don’t pretend to possess any bona fides. For expert opinion, I suggest two actual jazz musicians, friends, fine gentlemen, and fellow Substackers, Ethan Iverson and Vinnie Sperrazza. (Ethan was interviewed by Kaplan for 3 Shades of Blue and is quoted in the book, while Vinnie recently offered his own provocative review.) Me? I’m in the camp with the author of this article, which I assumed was from the Onion and not the Guardian when I read the headline.

Like Adrian Chiles, when it comes to jazz I feel like “There was so much I didn’t understand—including, frankly, a good deal of the music.” I adhere to his “three sections” theory, each piece consisting of opening and closing bits where the musicians play the same tune sandwiching the baffling but mesmerizing interlude where it sounds “to my untutored ear like a dozen or more players all playing whatever suited them.” I’ve thought often of this Tina Fey line from her show with Amy Poehler earlier this year.

What long-form improv and short-form improv have in common is that no one cares. Like jazz or sneezing, it’s a lot more fun to do than to watch.

I have never performed jazz. But I have done improv and suffer from ferocious allergies, and I think she’s on to something.

Take it with a grain of salt, then, when I say that Kaplan writes about music so evocatively that, as I did with his earlier two-volume biography, Frank: The Voice (2010) and Sinatra: The Chairman (2015), I kept a playlist close at hand so I could listen to individual songs and even entire albums immediately after he described them. Here he is on Davis’s 1958 rendition of “On Green Dolphin Street”:

Miles muffs the melody almost immediately, as he so often did to lay claim to a song, then continues his solo, which proceeds in different weathers, like an early-spring day with dark clouds scudding swiftly across a clear sky: by turns haunting, melancholy, joyous.

He notes how on “Limehouse Blues” from Cannonball Adderley Quintet in Chicago (1959), Adderley unleashes a “jubilant” solo.

Then Coltrane solos, and within seconds you realize that as adventurous as the alto solo had been, it had followed the chords of the song, and now the tenor player had led you off the map into his own rich and humid chordal territory, draped with sheets of sound like hanging jungle vines.

Above all, Kaplan knows how to place a quote for maximum effect. This one from Bill Evans will haunt me for the rest of my days.

I can remember coming to New York to make or break in jazz and saying to myself, Now, how should I attack this practical problem of becoming a jazz musician, as making a living and so on? And ultimately, I came to the conclusion that all I must do is take care of the music, even if I do it in a closet. And if I really do that, somebody’s going to come and open the door of the closet and say, Hey, we’re looking for you.

Kaplan writes that “One argument says that of this book’s three subjects, Bill Evans showed the least musical growth after Kind of Blue.” That may be true. But Evans’s Waltz for Debby (1962) was the first jazz album I ever bought. He served as my gateway to Coltrane, Davis, Parker, and Monk. You get there how you get there.

What I’m Drinking

Soon after linking to Jason Diamond’s essay on buying a round for the house, I found myself on the receiving end of the treatment for the first time. A place I haven’t visited in a while recently launched lunch service, which I used as an excuse to drop by. As I’d been thinking about Scott Scurlock, I ordered a Johnny Utah pale ale. That’s when a brass bell rang behind me. I turned to see two men looking sheepish, like one had dared the other and now both had regrets. But who can resist a brass bell?

Then a waitress approached. “These gentlemen are offering to buy shots for the house. Would you like one?” The late lunch crowd was small, and several of those present had already declined. Not me. I said “Absolutely” and ordered a rye for a bonus boilermaker.

I thanked the men at once, toasted them when my generous pour of whiskey arrived, shook hands with each as they left. “It’s a good day,” one of them told me. “Enjoy it.” I never found out what, if anything, they were celebrating. I do know that I had a huge grin on my face when it was my turn to depart, my entire afternoon reframed. It was a truly transformative gesture. I’m gonna ring that bell myself one of these days.

What (Else) I’m Reading

I love everything about David Pierce’s article for The Verge on the Excel World Championship, starting with the layout. Thanks to The Sunday Long Read for bringing it to my attention. If you’re not subscribing to SLR, you should think about it.

Jason Zinoman’s profile of Conan O’Brien in the New York Times revels in one of my favorite pieces of wisdom: “We don’t matter.”

Takeaways from this Hollywood Reporter interview with one of my artistic heroes, Steven Soderbergh:

Jettison the past

Books, not films

AI is horseshit

Taylor Swift will save us all

Also, his next movie is Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? with spies?!?

Kaplan’s comment about Bill Evans’ lack of musical growth post-KOB confuses development and maturity with changes in style, structure, and overall sound. Although Bill maintained the trio format in performance until his death, a deep dive into his catalog will reveal all sorts of what he used to call “inner development.” Kaplan’s remark also doesn’t take into account such outlier works as Bill’s collaborations with George Russell (Living Time) and Claus Ogerman (Symbiosis.) Just because Bill didn’t push his music into outer realms of the avant garde or jazz fusion, doesn’t mean that he didn’t grow and achieve “deeper” levels as an artist.

Beautiful Vince! Love that we see the Kaplan so differently…looking forward to the next one!