C&C 47: Not My Story to Tell

HOW TO ROB A BANK and my run-in with the Hollywood Bandit

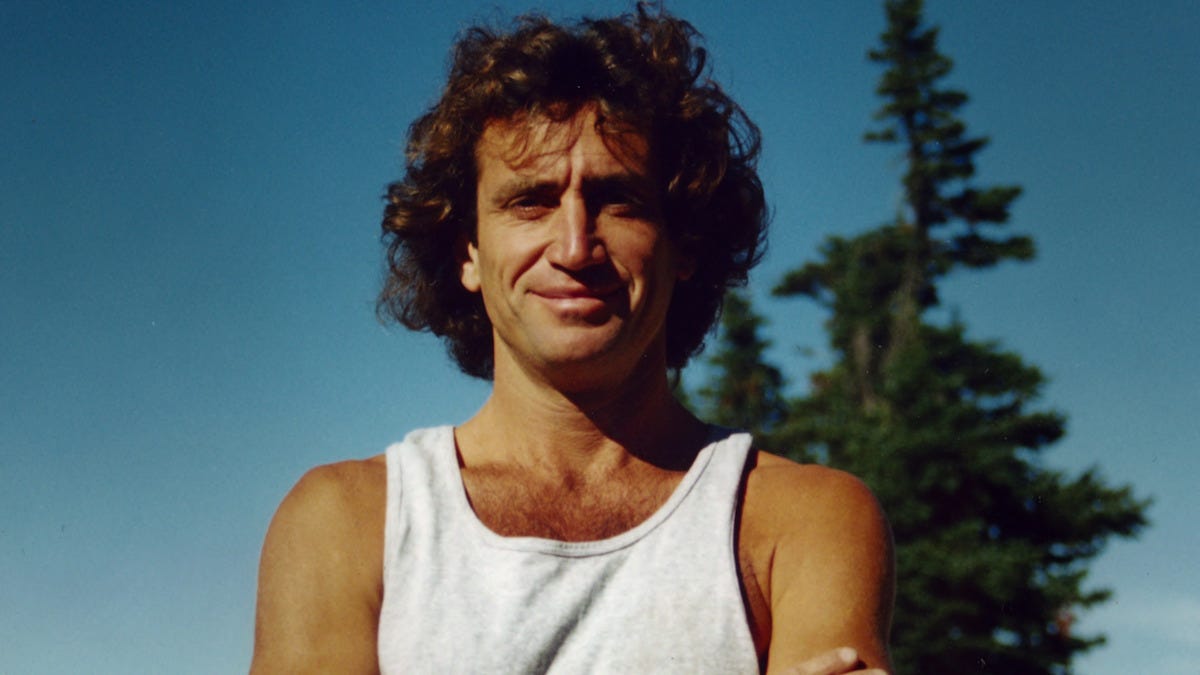

The new Netflix documentary How to Rob a Bank had a solid debut earlier this month, landing in the service’s top ten for over a week. It’s about the bank robber nicknamed “Hollywood” for his MO of donning theatrical makeup before pulling a job. He hit almost two dozen banks in the Seattle area from 1992 to 1996, a streak that netted over $2 million and put him atop the FBI’s Most Wanted list. That run ended on November 27, 1996, when law enforcement officers caught up with Hollywood and his accomplices after they’d taken down a North Seattle bank. The resulting manhunt bled into the next day—Thanksgiving—putting the entire city on edge for the holiday. (I was living here then, and remember it well.) Only after its resolution was Hollywood revealed to be Scott Scurlock, a charismatic nonconformist who lived in an elaborate multistory treehouse he’d built in the woods near Olympia, Washington.

I settled in to watch the documentary, directed by Stephen Robert Morse and Seth Porges, with more than the usual amount of interest. The first time I was hired to write a movie, it was about Scott Scurlock. Now I was watching someone else tell a story I’d put a few years into myself.

The chance actually came to me twice.

In 1997, I got a call from an entertainment lawyer I knew. He was sitting with Mike Magan, a detective with the Seattle Police Department who was an instrumental part of the Hollywood task force. Interest was swirling around the case so the lawyer posited that Magan team up with a writer and thought of me. Magan made a vigorous pitch about mismatched partners forced to set aside their differences to apprehend a skillful criminal escalating his game. But I’d followed developments enough to know that law enforcement could only be supporting characters here. Not with Scurlock involved, a man whose public persona—blending Peter Pan, Robin Hood, and the Pied Piper—masked a dark, controlling side. Who also, I remind you, lived in an enormous treehouse. After talking to Magan, I respectfully declined the opportunity.

A few months later, the lawyer called again, this time with a different client. He introduced himself.

“This is Charlie Frank,” he said. “You don’t know me.”

“Actually, I think I do,” I said. “You’re an actor. You played one of the Mercury 7 astronauts in The Right Stuff and The Young Maverick on TV, and you were in the sitcom Filthy Rich with Dixie Carter and Delta Burke before they did Designing Women.”

In the background, I heard the lawyer laughing. “I told you.” (I wasn’t done. Charlie’s wife, Susan Blanchard, is also an actor. When we met, I greeted her by excitedly saying, “You were in John Carpenter’s Prince of Darkness!” I try to make this tic seem charming.)

Charlie had largely stepped away from acting, but he was born and bred in Olympia and couldn’t resist the allure of a story set in his hometown. He had acquired the cooperation and the life rights of Scott Scurlock’s family and friends, and planned to make his directorial debut with a movie about his crime spree. We talked some more, he read my spec scripts, and he paid me, a twentysomething with zero credits, out of his own pocket to write the film. I will always be indebted to him for taking that risk.

I went down to Olympia. How to Rob a Bank reveals that Scurlock’s treehouse eventually collapsed, but at the time it was still standing, although a recent windstorm had shorn off the entire top floor. The structure was spread out across seven huge trees, featured working plumbing including a hot tub, and was equipped with multiple zip lines so Scurlock could flee the property instantly. It was the key to Scurlock’s mystique. Visitors routinely declared it an enchanted kingdom, while I could only gaze at it and think, Not up to code. Scurlock turned to bank robbery after the demise of his methamphetamine business—his partner, who sold what Scurlock cooked to a California motorcycle gang, was murdered—and had built his castle in the air like someone who routinely sampled from his own supply. The staircase to the lowest level, which extended several dozen feet into the air, had a handrail on only one side, and every step was a different height and width.

I clung to that handrail as Charlie and I made our way into Scurlock’s aerie. The property’s caretaker advised us not to venture any higher because of the storm damage. But I knew that Scurlock, whom everyone described as an adrenaline junkie, wouldn’t hesitate, so to prove myself I clambered up to the structure’s newly-exposed roof, taking in the verdant view as I skidded around in my Vans. I sat in front of the mirror that Scurlock used to apply his makeup before he rolled into a bank. And then I got to work.

There were complications. We learned that true crime author Ann Rule was writing a book about Scurlock. She had worked for the SPD and had many contacts there, so we narrowed our law enforcement perspective to the FBI. (To this day I haven’t read Rule’s The End of the Dream, published in 1998.) A Hollywood producer who had relocated to the Pacific Northwest glommed onto the project. He was annoyed that Charlie had already hired a writer and forced me off the movie. Charlie soon reversed course, bringing me back. Later, after turning in a draft that even the producer liked, I helped force him off the movie. I’m a quick study.

Scurlock’s family and friends were forthright in interviews, still at a loss to explain his double life. Frequently they’d punctuate a tale about his generosity or derring-do with “That was just Scotty,” but almost every anecdote betrayed a manipulative edge, a sense of a man forever testing how much those around him could be trusted. He would make a compelling figure to put at the center of a movie.

During a conversation Charlie and I had with Shawn Johnson, one of the FBI agents on the task force, I asked about the manhunt extending into Thanksgiving: “Did you guys get to eat?” Johnson said that residents of the Seattle neighborhoods being searched brought out food. He then sat back and reeled off the different desserts on offer that afternoon. “Haven’t thought of that in a while,” he said. I never felt more like a journalist. Afterward, Charlie punched me in the shoulder on our way out of the Federal Building. “Where’d you come up with that question? That detail’s going in the movie.”

Sadly, there wouldn’t be a movie. There was interest, and as Charlie put it, the tires were kicked more than a few times into the early aughts. But the 1990s vogue for low-budget crime films was over. My casting ideas may not have helped. I insisted that the perfect actor to play Scott Scurlock was Matthew McConaughey; he had the attitude and the build, the charisma and the darkness. The producer, then still attached, scoffed, “That guy’s already washed up.” I said, “You’re gonna think differently when he wins an Academy Award,” the producer looking at me like I was nuts. Who knows? If people had listened, the McConaissance might have begun a full decade earlier. And the world would be a very different place.

How to Rob a Bank tells Scurlock’s story well. It limits the use of reenactments, instead relying on animated storyboards. It’s a canny choice, given Scurlock’s mania for movies. As How to Rob a Bank emphasizes, he was inspired to take up his new career after repeated viewings of Point Break (1991), even emulating Patrick Swayze’s technique in his early heists, and he studied the robbery scenes in Michael Mann’s Heat (1995) obsessively. Both Magan and Johnson appear in the documentary, which clearly relishes the fact that they were intensely competitive then and don’t seem to care for each other now. The documentary probes some lingering unanswered questions, like who opened fire on the night of Scurlock’s final robbery.

It helps enormously that the filmmakers had access to material that we didn’t, like Scurlock’s journals. They were also able to talk to Scurlock’s accomplices, Mark Biggins and Steve Meyers, who were serving jail terms when we were developing our movie. I had to rely on their extensive interviews with law enforcement officials, which were part of the court records. The two men solve one mystery we never unraveled, which is how Scurlock progressed from robbing only the teller windows to knowing how to hit the vaults. I finessed the issue by having Scurlock turn to his contacts from the meth world, but Biggins and Meyers reveal that he had a source working for a bank who provided him with inside information, and that they kept her existence from the authorities so that she wouldn’t be charged as an accessory.

The movie’s most curious omission from my perspective is Scurlock’s girlfriend, who lived with him for extended periods during those years. On that Thanksgiving morning, when Scurlock had been identified but remained at large, FBI agents escorted her from the treehouse to Seattle so she could talk him into surrendering. Charlie had secured her cooperation, and she described the growing suspicion that Scurlock was concealing something from her and her reasons for ignoring the warning signs. Their relationship would have been the crux of our movie. She’s not mentioned in How to Rob a Bank. Maybe she declined to participate. Maybe the filmmakers felt her presence didn’t suit the story they wanted to tell. Maybe she’s not with us anymore and they never got to ask.

Late in the film, there’s a clip of Scurlock’s father, a minister, talking about his son. I recognized it instantly; it’s from one of the video interviews that Charlie shot. I was surprised and pleased to see it in this context, an artifact from our unmade movie surfacing in one that crossed the finish line. Charlie is acknowledged in How to Rob a Bank’s closing credits, as he should be. Several other people we spoke to are also in the documentary. It was strange to see them over two decades later, still talking about the man who altered the trajectory of their lives.

For years, I kept a box of research materials labelled Hollywood. Those video interviews, court records, pages of notes. Who knows? No movie is ever really dead, I told myself. Then, during a move a while back, I opted to toss it all. I had burned to tell this story once, and did to the best of my ability. But I wasn’t that person anymore, I wouldn’t tell it that way now, and I needed to let it go. How to Rob a Bank does justice to Scott Scurlock, so much so that I wouldn’t be surprised if it prompted some enterprising filmmaker to make a feature about him. Maybe Glen Powell is available. It’s too bad that whoever writes it won’t have the chance to climb that rickety staircase to Scurlock’s jerry-rigged haven. That perspective would be invaluable.

What (Else) I’m Watching

Speaking of Netflix movies, we fired up Under Paris (2024) expecting Friday night frivolity. A shark in the Seine? This’ll be hilarious! Reader, it was not hilarious. There’s some top-shelf scientific mumbo jumbo—I live for any movie with an expository speech building to the word parthenogenesis—but co-writer/director Xavier Gens (Frontier(s), Netflix’s Lupin) uses the goofy premise to grind multiple axes. It taps into the impotent rage about climate change as well as the wholesale revision of Paris that’s prompting residents to beg people not to visit the city for the Olympics and to threaten to defile the river this weekend. The catacombs sequence is authentically harrowing, and the wild ending is not at all what I expected. This movie is angry, and all the better for it.

Speaking of “Natural High,” which I actually was because that was the working title I gave to the Scott Scurlock script, reading Odie Henderson’s Black Caesars and Foxy Cleopatras sent me to Elvis Mitchell’s Blaxploitation documentary Is That Black Enough for You?!? (2022). There I learned of the existence of Train Ride to Hollywood (1975), a batshit musical starring R&B group Bloodstone, whose biggest hit was—you guessed it—1973’s “Natural High.” (Admit it, you didn’t think I was going to land that segue.)

In Train Ride, Bloodstone takes the title trip in the company of the biggest stars of the 1930s and ‘40s, along with “Marlon Brando” as the Godfather for some reason. No one famous is among the ranks of the impersonators, unless you count Phyllis Davis from Vega$ as “Scarlett O’Hara” and Jay Robinson, always Dr. Shrinker to me, as Bela Lugosi as Count Dracula.

This entire curio is on YouTube, and I recommend it for insane novelty value alone. It plays like a padded-out ‘70s variety show sketch; at one point, the entire cast leaves the train to take part in a send-up of vintage boxing films featuring an ersatz Howard Cosell. Around the 57:40 mark, after “Clark Gable” and “Jean Harlow” have been snuffed out by the Armpit Killer—yes, I’m aware of how that sounds, but go with me here—“Humphrey Bogart” delivers a eulogy accompanied by photos of the real actors that is oddly affecting. Tom Laughlin of Billy Jack fame distributed Train Ride to Hollywood, and the truncated release sounds nuts: Omaha-specific ads when the film was test-marketed there, and a three-theater world premiere in Detroit with Bloodstone and Jay Robinson helicoptered between venues.

Here’s Bloodstone with the movie’s best number, “Train Ride.” Please ignore that they are singing about heading to Hollywood while clearly in L.A.’s Union Station.

What I’m Reading

Jason Diamond, whose newsletter The Melt should be on your subscription list, wrote a sensational essay for Esquire on the lost art of buying a round for the house.

Thank you for the great article. I was in the US during that time but I don't remember the incident. I just saw the Netflix documentary and I found your article when I wondered why there was no movie about it. Such a pity that you threw away the materials. You could have made it a book! I still think it should be a movie.

Thanks for this article. Watched How to Rob a Bank and really enjoyed it. I thought Scott Scurlock looked a lot like Neal Cassidy.