C&C 46: Otash-orama

The real-life Tinseltown P.I. in a biography, a novel, and his own (?) words

Hollywood lore needs a figure like Fred Otash, the Los Angeles police officer turned shamus to the stars in the 1950s and ‘60s. A figure of questionable morals equally at home on mean streets and in night spots, it’s little wonder that he has inspired characters—Robert Towne drew on him in creating Chinatown’s Jake Gittes—and turns up on the pages of novels himself. A new biography, The Fixer: Moguls, Mobsters, Movie Stars and Marilyn (2024), doesn’t set the record straight so much as lean into legend.

Manfred Westphal, who cowrote The Fixer with Josh Young, had a movie-ready meet-cute with Otash in 1990; the detective had retired to the same swank West Hollywood condominium as Westphal’s mother. Then a studio development executive, Westphal spent years trying to sell Otash’s story to film or TV, and bases the book on Otash’s personal records. Here’s where the legend stuff kicks in: Westphal and Young note that Freddie’s “hot files,” kept under lock and key, were destroyed by Otash’s attorney upon his death in 1992, and that the recently-completed manuscript to Otash’s own tell-all memoir mysteriously vanished at the same time.

For all the highly-touted inside info, it’s the opening chapters of The Fixer about Otash’s LAPD stint and his clashes with then-chief William H. Parker that are the most illuminating. The show business sections offer little new material as they cover terrain familiar to scandal seekers: Otash’s work as “fact-checker” for Confidential magazine; the Lana Turner/Johnny Stompanato affair; the infamous “Wrong Door Raid” when a jealous Joe DiMaggio, accompanied by Frank Sinatra and others, barged into an apartment expecting to catch his wife Marilyn Monroe in flagrante delicto only to rouse a sleeping secretary.

As is evident from her billing in the subtitle, Monroe is the featured attraction here. Otash knew her well, and conducted electronic surveillance on her at the behest of the Republican Party. (The most fascinating tidbit in The Fixer is that so many interested parties had planted listening devices in Monroe’s home and that of JFK’s brother-in-law, actor Peter Lawford, that Otash didn’t have to install his own. He simply used his state-of-the-art equipment, concealed in a van disguised as a 24-hour TV repair truck, to tune into the frequencies of those bugs.) But don’t expect any bombshell bombshells; after pages of hype, Westphal and Young leave us with, “We will never know the truth. We will never know the full story.” The most damning revelations concern ABC spiking a segment of the newsmagazine 20/20 about Monroe’s death in which Otash finally spoke on the record in the 1980s. The writing becomes more overheated as The Fixer progresses, as if to compensate for the lack of investigative fireworks. Let’s take a spin with Lawford in the wee hours of August 5, 1962:

The palm-lined thoroughfares under a waxing crescent moon were practically deserted at this hour, the start of another sunny Sunday in a city whose somber beauty now juxtaposed the horror he had just witnessed: the world’s most famous movie star dying, or already dead, in her bed.

Then there’s the matter of an audio recording Otash allegedly made of Monroe’s final moments. Freddie cues up the tape:

Soon Otash would know everything, both the angels and demons who had taken part in the seismic event that would ensnare the world’s imagination for decades to come. He pressed play.

We never learn what’s on the recording, or what ultimately became of it. We’re left only with this choice bit of purple prose:

The celebrated Superman of sleuths, able to squash the tallest Hollywood scandal, now found himself grimly overwhelmed by a haunting salvo of kryptonite whose sheer possession could ruin him forever.

There are echoes of James Ellroy in that verbiage, which is only fitting given that Otash has appeared in Ellroy’s fiction. Given the author’s well-documented obsessions, how could he not? The two men talked collaboration. In The Fixer, Otash dismisses the novelist with a suitably Ellrovian epithet, branding the overture “‘a shill’ to feign friendship, to pump him for details and plunder his life for Ellroy’s personal agenda.” Ellroy, for his part, has said that Otash “was a con artist, bullshitter … I did not trust him not to dissemble. I got what I could, and he died.”

Otash appeared as a peripheral figure in Ellroy’s Underworld USA trilogy before moving to center stage with Widespread Panic (2021) and The Enchanters (2023). Maybe in fiction, as in life, the shamus operates better on the margins, because I read Panic when it came out and had zero recollection of it. Otash is long dead in the book and stranded in “Pervert Purgatory,” forced to recount (and recant) his sordid sins in order to move on in the afterlife. What follows is a symposium of sleaze featuring a cast of boldfaced midcentury names.

Allow me to reiterate: the book is narrated by a dead guy trapped in purgatory, which I somehow forgot. And I was raised Catholic.

Blame the lapse on my evolving relationship with the Ellroy oeuvre. His L.A. Quartet—The Black Dahlia (1987), The Big Nowhere (1988), L.A. Confidential (1990), and White Jazz (1992)—remains a crime fiction high-water mark, and American Tabloid (1995), the first Underworld USA novel, is a legitimate masterpiece. I tapped out of the subsequent entries, however, and what was once bruited as his Second L.A. Quartet has the queasy feel of an author churning out his own fanfic, with Ellroy shuffling characters from his previous work into a sprawling WWII home-front saga. Despite my inadvertent memory-holing of Widespread Panic, I decided to pick up last year’s The Enchanters, in which Ellroy ditches the celestial set-up to plunge headlong into the Otash/Monroe nexus following her death.

Reading it soon after The Fixer only highlights how much Ellroy has deviated from the historical record. One character describes Otash as “a well-known bird dog for Chief Parker,” while The Fixer fixates on Otash’s lasting animosity toward his old boss. The book is written in the first person, and while it makes sense that Otash would lapse into telegraphic, hopped-up-on-bennies Ellroy-speak, it remains jarring when famous people do it, like Roddy McDowall, spending his downtime on Cleopatra (1963) making a porn parody of same (the budget busting on that famous Fox flop factors into the convoluted plot), and Elizabeth Taylor, who delivers a lurid aria worthy of Kenneth Anger after bedding real-life baseball player Bo Belinsky—an assignation arranged by and, of course, secretly filmed by Otash. Freddie is the latest Ellroy character to exploit a memory technique pioneered by Hans Maslick, but this “self-taught eideteker” may be the first to keep repeating “Man Camera,” which sounds like something Tom of Finland would say to psyche himself up before a photo shoot.

What hangs over The Enchanters isn’t a dreary déjà vu so much as a clock-punching sense of obligation, as if Ellroy grew weary of hearing “You’ve gotta write your Marilyn book!” and took up the task to quiet the peanut gallery. The trouble is, he’s not interested in the subject. The Fixer’s Otash “had busted (Monroe), worked for her, counseled her, spied on her, been berated by her, and through it all, admired her.” Not so Ellroy’s version, who states bluntly:

I didn’t like her. I didn’t get her. Her acting chops and alleged va-va-voom hit me flat.

For the record, I side with the Demon Dog here. I, too, am impervious to Monroe’s charms. I understand the power of her story, which feels like a myth Hollywood commissioned about itself. But for whatever reason, I can’t surrender to it, and I’ve never been completely sold on her acting. As someone who has written about historical Hollywood personages in a criminal context a time or five, I empathize with the impulse to tweak their public images. But Ellroy’s take on Monroe—she “embraced the pervy Weimar Republic aesthetic” and became obsessed with sex criminals believing “banal brutality as the fount of true human horror and thus great art”—collapses under the weight of its unpleasantness. A sampling of sentiments about the former Norma Jean Mortenson, voiced by Otash and others in The Enchanters:

Marilyn was nothing but a glorified bait girl.

She gave herself up cheaply, in all ways.

She is nothing but a scene maker, as well as being the fantasist and premier bullshit artist of our time. That girl cannot stop lying.

She was a sick twist who craved sick attention.

She had succumbed to the idiot notion of being Marilyn Monroe, movie star and worldwide sensation.

This ceaseless disdain degrades Monroe and grinds down the reader. I felt grubby by the time I staggered to the end of The Enchanters. Maybe that was the point.

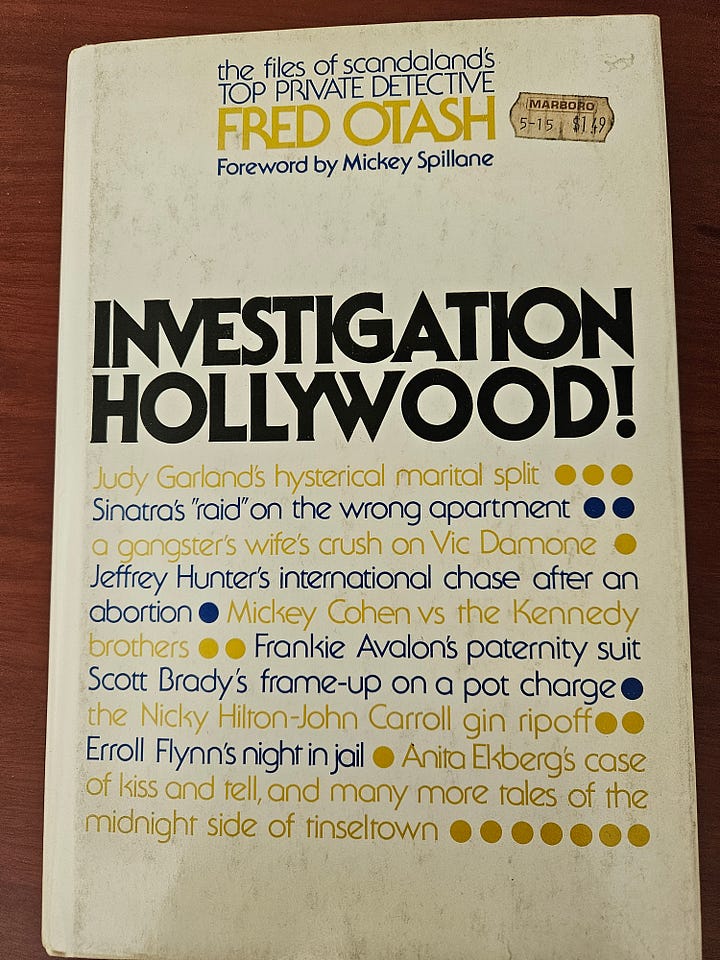

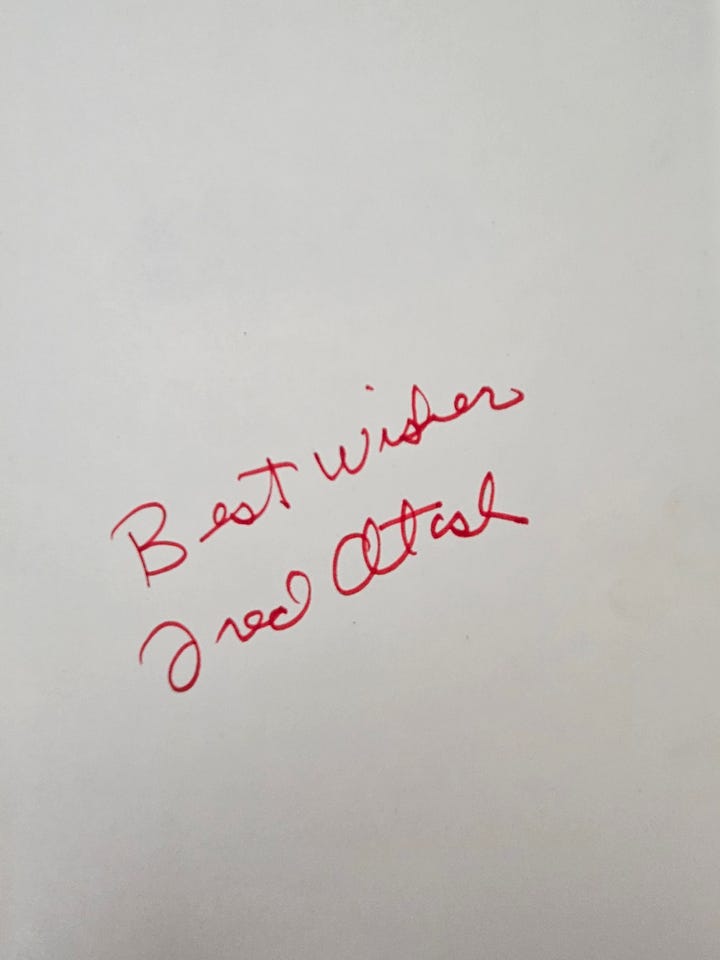

What would Otash would say about his own life? I dug out the copy of his memoir Investigation Hollywood! (1976) that I bought ages ago when I spotted it in New York’s Strand Bookstore. It’s even signed by Otash. At least, it’s signed by someone with a red felt-tip pen. Maybe that will be my hobby, stealthily autographing stock in used bookstores, grabbing reprints of O Pioneers! and scribbling Stay frosty, Willa Cather in Sharpie.1

Otash’s memoir is dedicated to the lawyer who torched his files and to Mickey Spillane, who contributed a foreword and “whose expertise and lingo are sprinkled throughout this book.” That could imply that Spillane had a hand in writing Investigation Hollywood!, but ghostwriting duties were actually performed by pulp author and Spillane crony David J. Garrity (aka Gerrity).

The Fixer dismisses Investigation Hollywood! as “sanitized,” which it surely is. But this is the Otash to spend time with, a figure fit to be a prestige TV antihero. He’s no tortured soul but a gleefully mercenary presence, untroubled by the compromises of his profession, happy to drop a name or two—especially when it comes to the actresses he squired around Los Angeles—and happier still to withhold the names but supply a barrage of heavy-handed hints. Both this book and The Fixer include a windy transcript of a conversation between Rock Hudson and his wife Phyllis Gates that reads like it was scripted by a UCLA psych undergrad who’d watched Spellbound too many times, the difference being that The Fixer identifies both parties. One of The Fixer’s stronger chapters covers Otash’s gig working for Judy Garland during a contentious stretch of her marriage to Sid Luft, but the episode is handled better in his supposedly whitewashed memoir. I know which book I’d reread. The best guide to Fred Otash’s seamy circuit was the man himself.

What I’m Drinking

After that, we could use a cocktail. Last week I had the pleasure of visiting the inaugural Chartreuse Dive Bar pop-up at Seattle’s Bad Bishop, organized in part by bartender and friend Matt Pachmayr. All of the drinks (and some of the nosh) featured the French liqueur, prized in this era of scarcity. I kicked things off with a Bougie Boilermaker—a shot of yellow chartreuse and a glass of champagne—that began the evening on a perfect note.

Matt also introduced me to the Love & Murder, a cocktail I wish I’d been able to spotlight in my Noir City column for the handle alone. The taste is also worth talking about. The drink, created in 2021 by Nick Bennett of New York’s Porchlight, pairs green chartreuse and Campari, two liqueurs most often used as modifiers, in a dazzling pas de deux. Don’t skip the saline solution, essential to balancing herbaceous and bitter.

Love & Murder

1 oz. green chartreuse

1 oz. Campari

1 oz. lime juice

¾ oz. simple syrup

4 dashes saline solution (5:1 water to kosher salt)

Shake. Strain. No garnish.

For the record, I confirmed the authenticity of Otash’s signature by comparing it to a copy of Investigation Hollywood! sold on eBay, which he’d inscribed: To Mike Connors, From one private eye to another, Freddie Otash. He’d signed the book to freaking Mannix!

I think the insight that Otash "operates better on the margins" succinctly sums up the problem with these recent Ellroy books. I couldn't make sense of Widespread Panic, which left me wondering whether I was supposed to. (I thought maybe Ellroy was putting a lot of himself into his Otash character, for better or worse.) I happened to be in middle of reading The Enchanters right now - but why is it taking me so long to get through it?. Thanks, think I will subscribe!

Great piece on an obscure personage I always wondered about. Sadly, I endorse this take on James Ellroy...