C&C 33: Reheated Chili

I remember there’s a sequel to GET SHORTY, both book and film, plus I go to rum school

It’s one of the minor joys of flipping channels lost in the streaming era: stumbling onto a movie right when a good part starts. A repeat offender for me is Get Shorty (1995), based on Elmore Leonard’s 1990 novel. The film consists of nothing but good parts; I stop to watch one scene and invariably leave it on until the credits roll.

The novel remains one of Leonard’s strongest, likely because there was personal motivation involved. Shorty, which follows Miami shylock Chili Palmer as he pursues a runaway client to Los Angeles and discovers his skillset transfers to the movie business, was sparked by Leonard’s interactions with Dustin Hoffman during an abortive adaptation of his 1983 book LaBrava. It’s easy to envision the actor as the height-challenged, mercurial superstar Michael Weir, rechristened Martin in the movie.

The guy had to be up in his late forties but looked about thirty-five. Not bad looking, thick dark hair he wore fairly long, kind of a big nose. There was that Michael Weir twinkle in his eyes, Michael telling his many fans he was a nice guy and didn’t put on any airs.

Rereading the book recently compelled me to watch the movie again, this time deliberately and from the beginning, like you’re supposed to. Screenwriter Scott Frank earned an Academy Award nomination for Out of Sight (1998), based on Leonard’s 1996 book. I’d make the case that while Out of Sight is the better movie—with Steven Soderbergh behind the camera, how could it not be—Shorty is the more impressive adaptation. Frank had more characters to corral, a broader canvas to compress. Take the brilliant opening sequence, which conveys a wealth of information in engaging fashion, establishing contentious relationships with ease. On this viewing I was struck by how much of the film’s dialogue, including many of the lines expertly thrown away by Delroy Lindo as Chili’s nemesis Bo Catlett, come straight from the novel. Frank has an ear for the music of Elmore Leonard, and the near-perfect cast led by John Travolta as Chili plays like a time-tested ensemble.

Leonard wrote a sequel to the book, which was duly turned into a movie. All I remembered about both was that I didn’t care for either. But I revisited them as well, because this is what January does to me.

Get Shorty, the novel, closes with Chili grousing about how tricky endings are. Be Cool (1999), the book, opens with him observing that a sequel isn’t exactly a picnic; it “has to be better’n the original or it’s not gonna work.” Such meta references are appropriate for a novel that essentially dramatizes Leonard’s modus operandi. In an interview with Martin Amis, he said:

I start with a character. Let’s say I want to write a book about a bail bondsman or a process server or a bank robber and a woman federal marshal. And they meet and something happens. That’s as much of an idea as I begin with. And then I see him in a situation, and I begin writing it and one thing leads to another.

Chili’s approach to “playing with an idea” in Be Cool is identical. “Look, the way I work, I begin with a character instead of a plot, someone in a job that a plot might come out of.” Someone like Linda Moon, a dating service employee who moonlights as a singer. Chili’s already intrigued by the music business, seeing as he was on his way back from the men’s when wiseguy-turned-record-exec Tommy Athens was gunned down outside a coffee shop. Why not take over Linda’s contract, shepherd her into the industry, see what develops.

Chili is between projects at the moment. Having worked out how his own story ended in Get Shorty and turned it into a hit film, he let the studio strongarm him into doing a lousy sequel. (It’s a running gag in Be Cool that the bad guys universally praise the lame follow-up: “You can do a lot with amnesia once you get it going.”) Leonard fights that same fate here, pushing his most beloved character into new territory in the hope of keeping things fresh.

Leonard never wrote a boring book, but Be Cool comes close. The pages dedicated to music biz minutia are better suited to an extension course. The plot hinges on a massive coincidence. Worst of all, the record industry heavies never seem worth Chili’s time. Novelist Larry Beinhart (Wag the Dog) wrote that “the basic structure of an Elmore Leonard plot is that a big tough guy pushes a little tough guy. The little guy doesn’t take it. He shoves back.” Chili, with a hit movie under his belt and Tinseltown players taking his calls, isn’t a little tough guy anymore. Still, there are pleasures throughout. Before getting plugged, Tommy praises Chili’s first film in true Hollywood fashion: “I know you did okay with Get Leo, a terrific picture, terrific. And you know what else? It was good.” Linda Moon’s sound, described as “AC/DC meets Patsy Cline,” seems unlikely to chart, but she’s a nicely prickly presence, believable as an artist. (Leonard ties the character’s name into his 1985 novel Glitz.) Having broken up with actress Karen Flores, Chili enters a nuanced adult romance with a studio executive as he waits to see how his latest yarn ends. He has a plan if he doesn’t like what happens: “Then we do it the old-fashioned way, let the screenwriter think of something. Scooter, the same guy who wrote Get Leo.”

“Scooter” Frank didn’t adapt Be Cool (2005), so the movie begins behind the eight ball. (Peter Steinfeld does the honors.) Utterly dooming the enterprise is the decision to forego an R rating in favor of a PG-13. A decent joke up top burns the film’s sole allotted use of the F-word to acknowledge the challenge ahead. There’s no such thing as PG-13 Elmore Leonard. Consider this sampling of Get Shorty dialogue delivered with gusto by Dennis Farina as Ray Bones, heights that the neutered Be Cool cannot even contemplate scaling.

e.g., i.e., fuck you!

They say the fucking smog is the fucking reason you have such beautiful fucking sunsets.

Fuck you, fuckball.

Those lines get to the heart of why the adaptation of Be Cool falters. Get Shorty’s heavies, Farina and Lindo, are funny and scary simultaneously, while the sequel’s grab bag of goons only manages to be irritating, a swarm of gnats to be swatted away from Chili’s face. (An ambitious Black talent manager who is one of the book’s better villains is played, in a bizarre piece of color-blind casting, by Vince Vaughn.) Chili forsakes the movie business here, going all in on turning Linda Moon (Christina Milian) into an MTV superstar, so naturally all of her thorniness has been pruned away, the character turned into an angelic cipher of boundless talent.

Changes to the story mean that Chili now takes up with Tommy’s wife Edie (Uma Thurman), clad in T-shirts reading Mourning and Widow as she tries to run the record label herself. There’s an interminable sequence featuring Travolta and Thurman cutting a rug to the Black Eyed Peas and Sergio Mendes clearly meant to evoke memories of the twist contest at Jack Rabbit Slim’s in Pulp Fiction (1994). But all it does is set up a full-cast dance party over the closing credits that has the jollity of a team-building exercise at a corporate retreat.

In a movie with its share of cringeworthy scenes—Harvey Keitel rapping?—comes a doozy. Aerosmith’s Steven Tyler, playing himself (astoundingly reprising the cameo that Leonard wrote for him in the novel), smokes cigars with Chili after a Lakers game, listening with Churchillian intensity as Chili suggests that the band’s 1975 hit “Sweet Emotion” is, in fact, about Tyler’s love for his daughters. Tyler grudgingly agrees. I searched in vain for a shoebox with holes poked in it through which I could view this confab so as not to permanently damage my retinas.

My advice if you want to watch a comic crime caper set against the backdrop of the L.A. music scene that includes André Benjamin, aka André 3000, in the cast? Check out Ron Shelton’s Hollywood Homicide (2003), about which I’ve written before. My real advice? Watch Get Shorty again and appreciate the way a visual fabric is maintained while the metaphor plays on different levels.

What I’m Drinking

I’ve never worked a day behind a bar, but I have what’s known as bartender’s profile when it comes to cocktails. I like ‘em brown, bitter, and stirred, my eye drawn to whiskey drinks first.

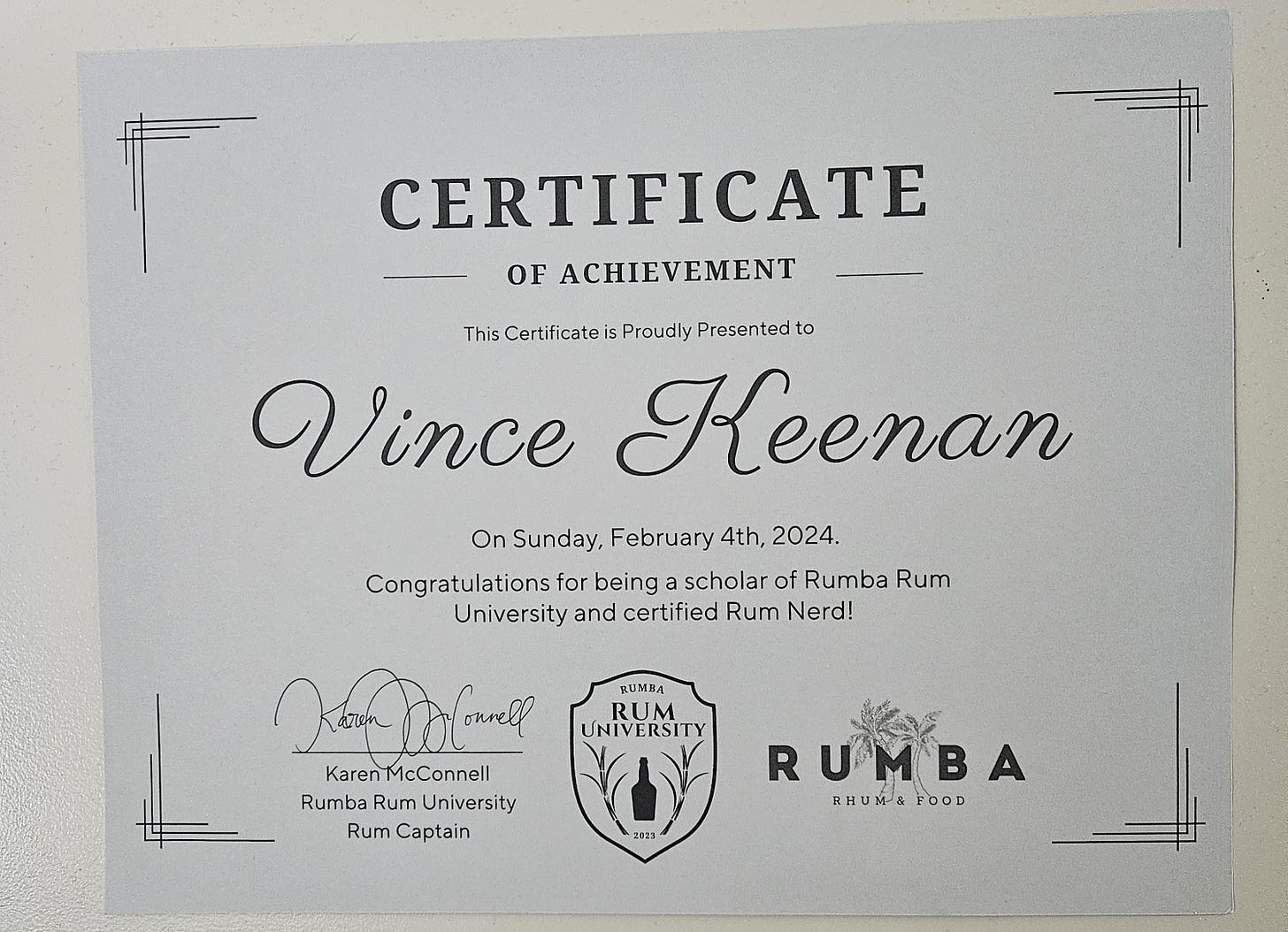

Which makes rum something of a blind spot for me. I love it, but don’t know enough about it. Fortunately, Seattle is home to Rumba, one of the world’s foremost rum-centric bars. Even more fortunately, earlier this year they offered their Rum University, the intensive program all of their bartenders must take, to the public for the first time. And you know me. I’m a lifelong learner.

Karen McConnell, Rum University provost and the bar’s rum captain, led an intensive five-week course that ranged around the Caribbean and the Americas, spotlighting Barbados and Jamaica one week, Guyana and Martinique the next. The accompanying tastings emphasized the unique terroir of each locale, best exemplified by our closing week tour of clairin, the traditional spirit of Haiti. (I can also attest that sampling several ounces of quality rum on Sunday afternoons puts you in a far different frame of mind as the work week begins.)

I appreciated how the lessons directly addressed rum’s dark history—the spirit would not exist in its current form without slavery and colonialism—while never losing sight of how integral it is to Caribbean culture, and how much pride the people who make it take in its production.

The course confirmed my bias toward rhum agricole, a lighter, grassier variety made from sugar cane juice instead of molasses. Much of it comes from Martinique. I finally purchased a bottle for my home bar so at a moment’s notice I can prepare a ‘Ti Punch, the beverage of choice throughout the French West Indies. Opinions vary on the use of ice and sugar, prompting the now-famous phrase Chacun prépare sa propre mort, or “Everyone prepares their own death.” Below is my personal means of destruction.

And yes, I did receive a certificate upon graduation. I have no idea where my college diploma is, but my Rum U. sheepskin will hang in a place of honor. Probably over the home bar.

The ‘Ti Punch

2 oz. rhum agricole

¼ oz. simple syrup

1 lime coin (a slice of lime with pulp still attached)

Squeeze the juice from the lime coin into a rocks glass. Add the simple syrup. Combine with a swizzle stick (or a bois lélé). Add rum and ice. Stir. Garnish with another lime coin if you feel like it.

Where I’ve Been

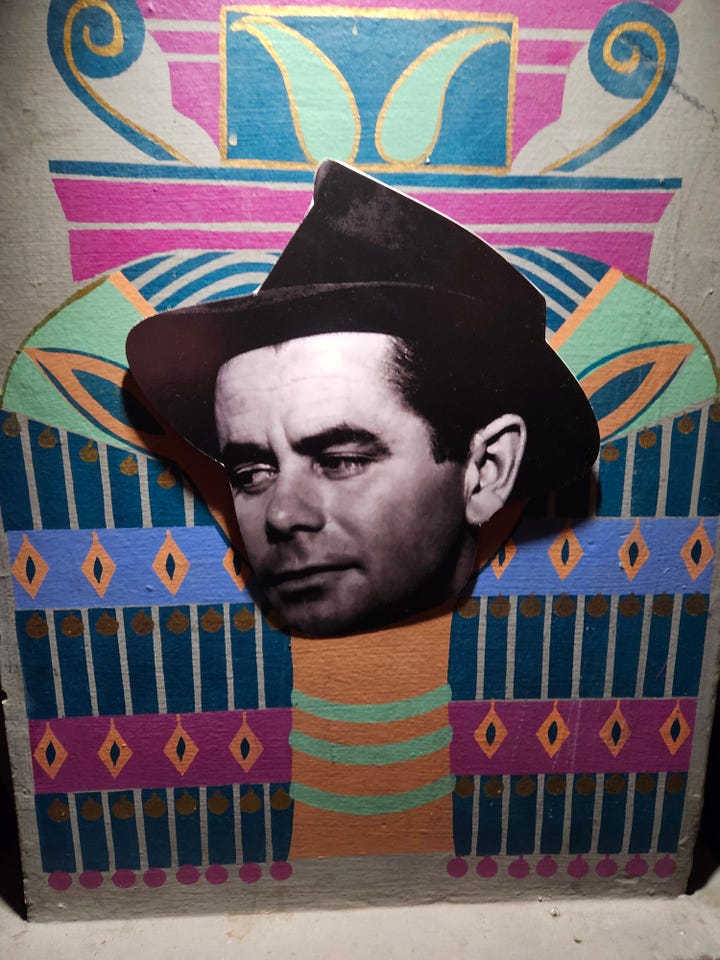

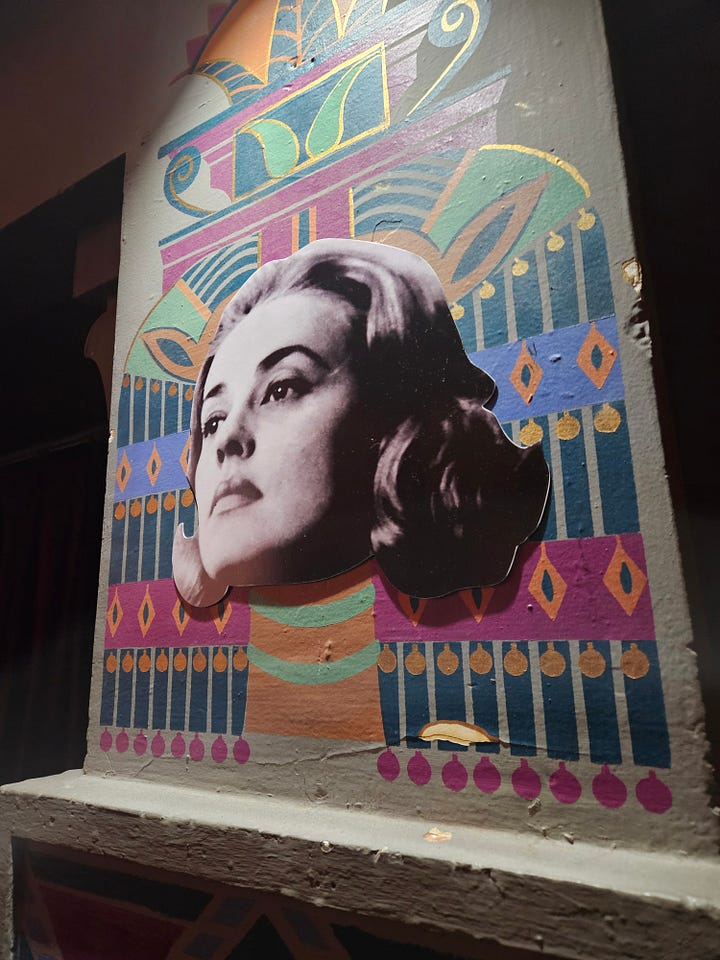

That’s a wrap on Noir City Seattle for 2024, the 16th iteration of the festival. It was a pleasure to stand in for my friend Eddie Muller as host for the final four days, introducing audiences to the stylish Sixties mayhem of Symphony for a Massacre (1963) and seeing a pristine print of the tough, long-out-of-circulation Edward G. Robinson jailbreak film Black Tuesday (1954), among other titles. My thanks to Eddie and everyone at SIFF Cinema. I’d especially like to thank the staffers who added these faces to the Egyptian’s décor.

Clockwise from upper left: Glenn Ford in Human Desire; Jeanne Moreau in Elevator to the Gallows; Ninón Sevilla in Victims of Sin; Marilyn Monroe in The Asphalt Jungle.

Great movie review. Love reading a good critique from someone who isn’t more invested in kissing their subjects’ bottoms, than conveying an honest opinion.

Your favorite drink may be similar to Brazilian caipirina made with. Cachaca and muggled lime.