C&C 64: Chasing Shadows

Two recent biographies have their work cut out for them, plus my best movie day in years

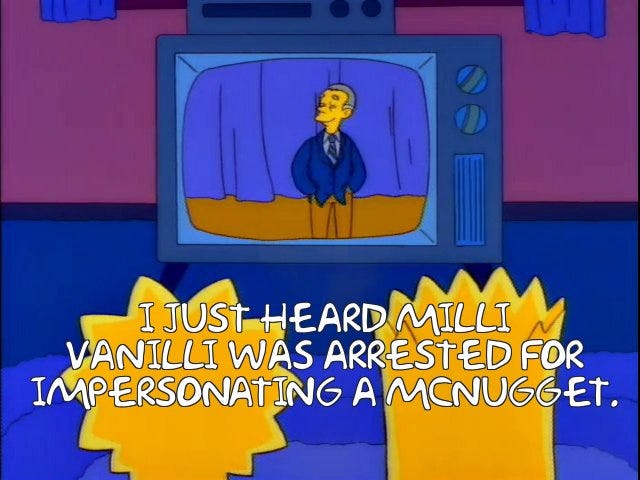

My experience of the hegemony of Johnny Carson’s The Tonight Show is best summarized by a gag from “Lisa’s Pony,” a season 3 episode of The Simpsons.

I grasped Carson’s significance, the staggering achievement of being the face of late-night TV. But to me—and many of the Simpsons writers—he was the guy who came on before David Letterman. One of those writers, Conan O’Brien, would take over Dave’s show. Even the hard-bitten Simpsons crew eventually changed their tune. One season later, in “Krusty Gets Kancelled,” Johnny made one of his only post-retirement appearances, with Bart suggesting that he might be the world’s greatest entertainer.

Carson the Magnificent (2024), by Bill Zehme with Mike Thomas, is one of the more confounding books I’ve read recently. That’s partly due to its own tragic history; Zehme, a gifted writer and Carson savant, labored on it for a decade only to die of cancer before he could complete it. His assistant Thomas took it over the finish line. Zehme penned pyrotechnic prose, and while Thomas made the wise choice not to imitate it, the seams regrettably show. But the book baffles mainly because of the contradiction intrinsic to its subject. Zehme writes that Carson was “the ultimate Interior Man, large and lively only when on camera,” that “to some degree, he was the man who wasn’t there, except that he was always there, night after night, making nationally televised mirth.” What he did is more interesting than who he was, a tough row for any Boswell to hoe. Zehme cannily exploits Johnny’s lifelong interest in magic as a psychological skeleton key, and there’s no denying that Carson’s vanishing act, walking away from public life along with The Tonight Show, was an admittedly impressive finale. But it hardly provides galvanizing reading.

The book also fails to make a case for Carson’s prowess to people who have no sense of him as a performer, a number that will only grow larger. In a sense, it can’t, given the nature of Carson’s talent; Zehme writes that “while his greatness had no expiration date, his art needed one in order to be great. When it mattered the most, he was transient as a breath, and every bit as vital.” Johnny himself knew what fate held in store. In Zehme’s celebrated 2002 profile in Esquire, marking the ten-year anniversary of his taking “the powder of all powders,” Carson mentions a famous radio star of his youth then amiably grouses that “Nobody knows who the hell Fred Allen is anymore.” Obscurity comes for us all, no matter our Q rating. Reading the book, I was reminded of a 2019 interview with Conan O’Brien—you remember, the Simpsons writer who took over for Letterman—in which he delighted at Albert Brooks’ advice to embrace being forgotten, saying, “In 1940, people said Clark Gable is the face of the twentieth century. Who fucking thinks about Clark Gable?” Legions of TCM fans took to social media to miss Brooks’ profound point. Carson, to his credit, seemed secure in his accomplishments and unconcerned about his legacy.

Which still exists. Vintage Tonight Shows air six nights a week on Antenna TV. They’re mainly from the 1980s and early ‘90s, when the show was running on autopilot. I’d be more interested in the 1970s iteration, when Carson, in the words of writer Jason Zinoman, “was more willing to talk at length with Truman Capote about capital punishment or suddenly decide to ask every guest on an episode what they recall about their sixth-grade teacher.” I tune in on occasion but never make it very far, which isn’t surprising. Talk shows are ephemera, not meant to last. Letterman now has a FAST channel on Samsung TV Plus, and I won’t be looking in on that, either; that party, too, has ended. The greatest contribution the talk show has made to popular culture is The Larry Sanders Show, Garry Shandling’s behind-the-scenes sitcom, which I’d rank in the top three series of all time.

Still, I’m always up to watch Carson or any other host square off against Charles Grodin, a first-rate guest who lived to puncture the pretense of the format. Johnny was game to play along, as in the above show from 1990, telling Grodin, “I gotta do an hour a night. I’m looking for warm bodies … I know all the tricks. I always look alert, and I don’t care.” It’s the essence of Zehme’s book conveyed in mere minutes. Although Grodin, who’s promoting Taking Care of Business—cowritten by J.J. Abrams!—here, calls the film “probably the most entertaining picture I’ve done since Heaven Can Wait,” which is both untrue and blatant Midnight Run erasure.

Speaking of talk shows and erasure, imagine my surprise to learn that in 1959, Dorothy Parker appeared on David Susskind’s Open End with fellow guests Truman Capote and Norman Mailer—and that nobody knows what they talked about, because no copy of the episode exists. It’s an apt tidbit to be featured in Dorothy Parker in Hollywood (2024) because it underscores biographer Gail Crowther’s thesis: that much of the life of one of the leading lights of American letters remains obscured.

“Parker is a classic case of the misunderstood woman,” Crowther writes. “She was a problem, and a problem that simply didn’t fit in one way or another.” Parker frequently created that problem herself, as Crowther details her “habit of being extremely nice to somebody’s face, then eviscerating them the moment they left the room” if not before, as well as the alcoholism that lent “a hallucinatory, confusing, and chaotic feel” to her final years. Crowther also explores how men routinely failed to take Parker seriously, dismissing her multiple suicide attempts as bids for attention and questioning her enduring commitments to political causes: “There was something wonderfully bewildering about a woman who would spend hundreds of dollars on one piece of elegant lingerie while equally funding several socialist campaigns.” Above all, Parker was remembered for bon mots at the Algonquin Round Table that she loathed rehashing, because that era was never as much fun as the public thought it was, or Parker herself wanted it to be.

Focusing on Parker’s years as a screenwriter—her credits include the original A Star Is Born (1937), Alfred Hitchcock’s Saboteur (1942), and the Oscar-nominated Smash-Up, the Story of a Woman (1947)—not only gives the book a welcome shape, but provides a singular perspective on Parker and her talent. Not to mention some choice details. I liked learning Orson Welles, a Parker pal, was at one point sharing a bungalow “with two other writers trying to update the Lord’s Prayer, which he wanted to adapt into a movie.” Even in the ‘40s, IP was king. (I am obligated to observe that Parker makes a cameo appearance in Dangerous to Know, the second Lillian Frost & Edith Head mystery by Renee Patrick.)

What I’m Watching

For once, you can genuinely describe a movie as one of a kind. Eno (2024), Gary Hustwit’s documentary about musician/producer/artist Brian Eno, uses generative software to create each screening based on hundreds of hours of footage, so that the film is literally never the same twice. For that reason, it’s unavailable to stream, but last weekend Hustwit arranged a special online event, with six distinct iterations of Eno streaming over the course of twenty-four hours. Rosemarie snapped up a ticket. We took in one screening, the film running about eight-five minutes. She tuned in to a showing the following morning and watched for almost half an hour before encountering material we’d already seen.

The innovative format suits a portrait of a polymath. In our screening, Eno (in a succession of impressive shirts) discussed: his early films made with a video camera bought from a roadie for the band Foreigner; how to bring about world peace by increasing the number of singing groups; his efforts to make painting more like music, and music more like painting. Also heard from were several of his collaborators, including David Bowie, David Byrne, and members of U2.

At one point, Eno demonstrated a double pendulum, saying that it serves as a visual reminder that we act as if we’re operating in linear systems when we’re always moving through complex ones. I have not been able to get this metaphor out of my head, and feel like it explains so much. That scene alone would have been reason to watch Eno, but the entire enterprise was fascinating. It’s worth signing up at Hustwit’s website to learn when the film will be screening again.

The documentary ended early enough for us to queue up a second movie. It’s hard to believe that Night Call (2024, on demand) is cowriter/director Michiel Blanchart’s debut. Set in Brussels on a night when Black Lives Matter protestors have taken to the streets against police brutality, it follows young Black locksmith Mady (Jonathan Feltre), tricked into letting a woman into a stranger’s apartment where she promptly makes off with a stash of cash. The gangster who was indirectly robbed (Romain Duris) gives Mady until morning to recover the money. Feltre is hugely appealing, Blanchart finds the humanity in every character including Duris’s natty crime lord, and the action culminates in an appropriately uneasy ending as the sun comes up. If I see a better double bill in 2025, well, I’ll be happy about it.

I've seen snippets of old Tonight Shows and was struck by how long the conversations went on and that they were actually about something.

What stunned me about Carson was that supposedly his mother never acknowledged his success and he was never able to please her.