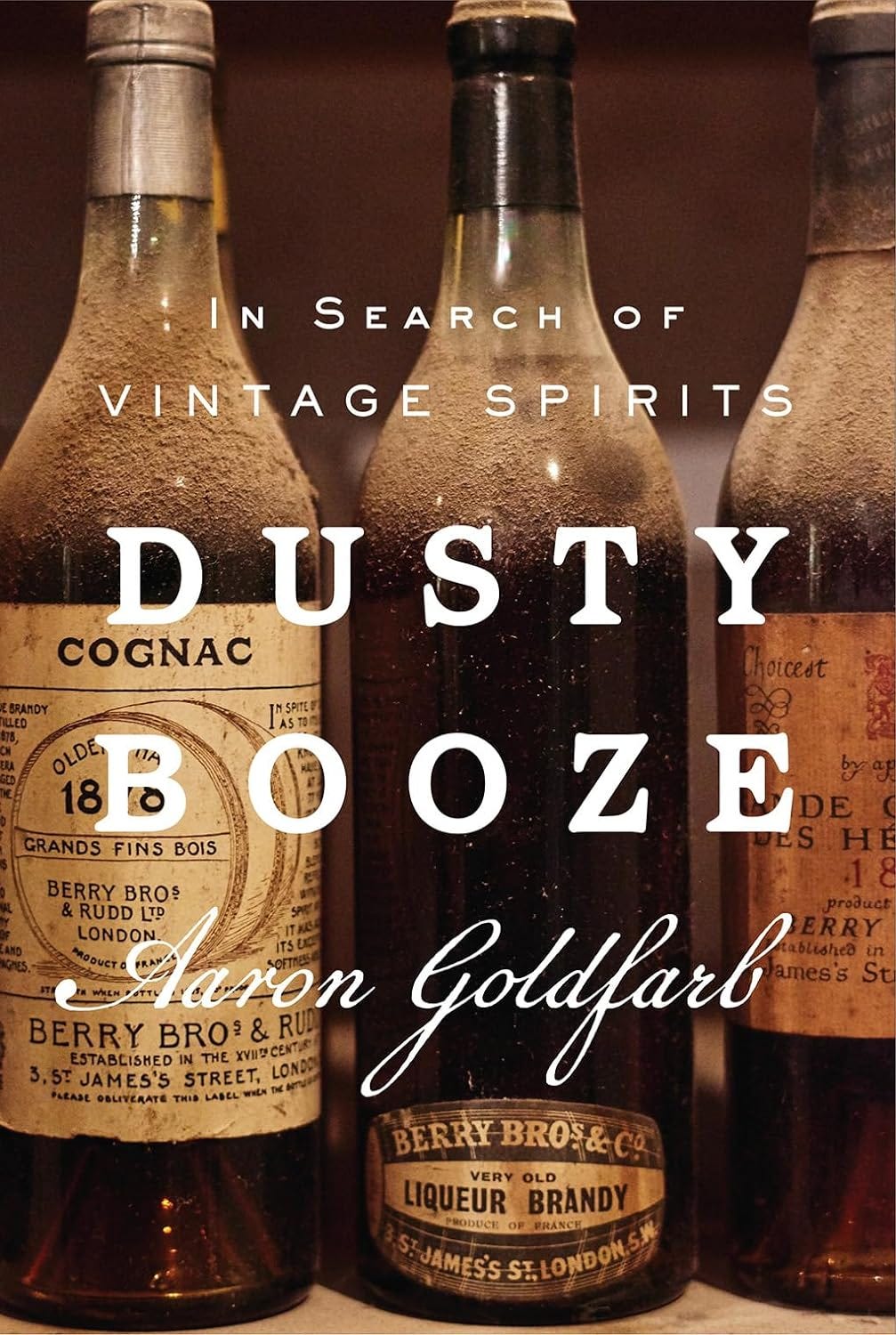

For whatever reason, I lack the collector’s impulse, even when it comes to things I love. So it was a fascinating trip to terra incognita reading Dusty Booze: In Search of Vintage Spirits (2024), Aaron Goldfarb’s foray into the world of “dusty hunters,” who venture to remote liquor stores, estate sales, and some truly unlikely venues for bottles of the hard stuff. According to Goldfarb, practitioners of this trade “are interesting characters, no question, Indiana Jones mixed with Comic Book Guy from The Simpsons with a dose of John Laroche from Susan Orlean’s The Orchid Thief,” and he captures their quirks and passions with vivid prose. He even succumbs to the fervor himself.

It’s easy to understand why. As Goldfarb explains, “Vintage spirits are drinkable time capsules,” adding, “A spirit is alive only for those years it is in a barrel; once it is bottled, it becomes like a mammoth locked in permafrost.” Pour some of that spirit out, though, and for the duration of a glass, it’s as if the mammoth again roams free, the intervening decades a mere pause.

Goldfarb initially concentrates on American whiskey, long the most active vintage market. It’s astonishing to learn that many experts have declared “the best thing they ever drank” to be the ten-year-old bourbon in the thirty-two chess-piece decanters of the Old Crow Chessmen set, which, when complete, also includes “a 45ʺ x 45ʺ chessboard made of deep-pile carpet.” Goldfarb then widens his focus to other tipples, offering primers and hints. Vintage tequila is shaping up as the next big category, while “another seller I spoke to sees vintage vodka becoming critical for Rat Pack cosplayers, a group I hadn’t realized was so prominent and one whom I hope to never encounter.” Dusty Booze is rollicking and ultimately moving, a celebration of the quest for something that endures in an age of the disposable, and of the understanding that, in the words of esteemed bartender and vintage spirits pioneer Salvatore Calabrese, in the end, even “the dust has value.”

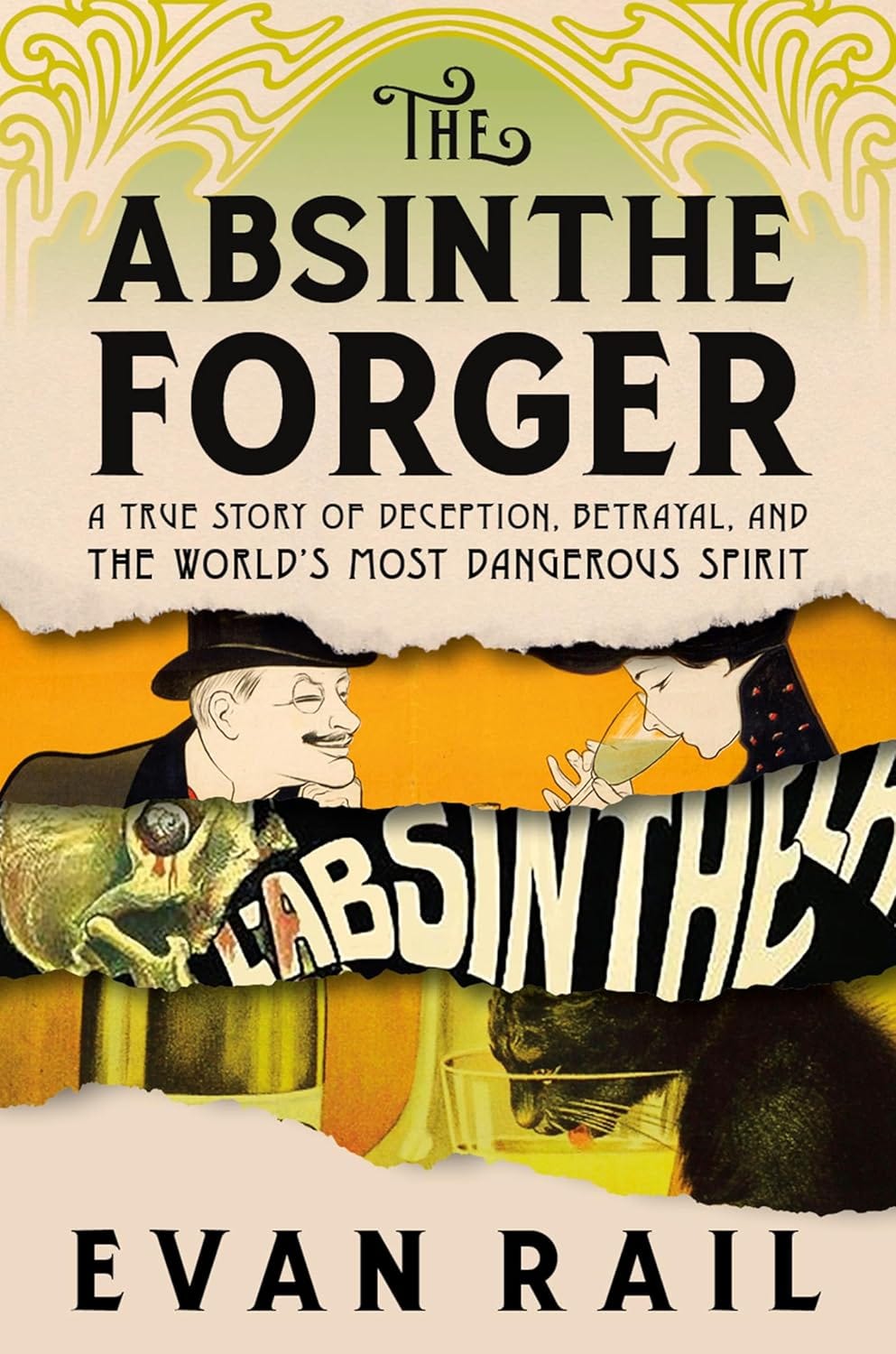

It may be true that, as Goldberg writes, “until very recently, fakes were not really an issue in the bourbon world.” But as the title of veteran spirits and travel writer Evan Rail’s forthcoming The Absinthe Forger: A True Story of Deception, Betrayal, and the World’s Most Dangerous Spirit (Melville House, October 2024) indicates, such is not the case on every other shelf of the liquor store. Rail investigates the curious career of a counterfeiter of “historic absinthes that were supposed to date from before the drink was banned and its production ended in France in 1915.” Adding to the case’s complexity: not only was the forger, referred to only as “Christian,” regarded as an authority in the tightly-knit world of absinthe aficionados, but he was even known to Rail.

In unraveling the mystery, Rail explores absinthe’s controversial and largely undeserved reputation. He also incorporates welcome flashes of autobiography, detailing the lot of the freelancer in the modern media environment and admitting that he investigates the matter partly because he longs to follow a story all the way to the end. Christian did not merely commit fraud but also damaged what had been an open and vibrant community of enthusiasts, and Rail considers that toll, too. The forger remains an elusive presence, which may frustrate readers craving justice, but Rail establishes early on that he’s not only writing about a crime, but the deeper obsessions present in Dusty Booze. Here’s Rail after sampling a jewel of one collection:

I had the sense of not just looking into the past or studying it from a reserved, academic distance, as I had with literature in Paris, but of tasting something so intense and strange that it did not feel like the bottle had passed through the centuries into our present day. Instead, the elixir in the bottle seemed to carry us backward into the past from which it had come.

Reading these books close together made an impression on me. And at a vulnerable time, too, because I had a birthday last week. After last year’s gift of improv classes, I wasn’t planning to splurge on anything. But both of these titles extol the virtues of drinking something older than you are, an experience I’d never had. And I’d reached an age where that already-pricey proposition was only going to get pricier. As Goldfarb writes, “Time is always marching on. You can’t stop it. You can’t control it.”

I knew where I’d go if I wanted to indulge. The Doctor’s Office, a jewel box of a bar on Seattle’s Capitol Hill, seats a mere twelve customers and is co-owned by an actual practicing physician. Its spirits collection is regarded as one of the most extensive anywhere, and the hospitality is first-rate; you’re greeted with a glass of champagne, and once the bartenders understand your preferences they will happily offer a “prescription,” a cocktail tailored to you. An appointment at The Doctor’s Office had been part of my last few birthdays, and I idly thought that this year I’d take a gander at their vintage offerings. Out of curiosity, you understand, nothing more.

But a thread woven through the narrative of Dusty Booze piqued my interest: the pending auction of a cache of liquor belonging to a Hollywood luminary. Eventually, Goldfarb turns over the cards. The booze ended up at The Doctor’s Office.

And it belonged to Howard Hughes. Aviator, playboy, and movie mogul.

The provenance of the potables was never in doubt. The bottles had been found at Hughes’s former Hollywood headquarters, a stone’s throw from the famed Formosa Café. Whether he drank from the stash was unknown, but he’d definitely paid for it and kept it in his possession.

I am not one given to grand pronouncements. But if there’s a list of people who should drink Howard Hughes’s hooch, my name is on it. And fairly high up.

As Renee Patrick, I co-write novels set in the Hollywood of the 1930s and ‘40s, when Hughes was throwing his weight around. The Film Noir Foundation, an organization I’ve worked with for the better part of two decades, regularly screens movies made at Hughes’s RKO Pictures, which FNF honcho and TCM’s Noir Alley host Eddie Muller has crowned “the House of Noir.” And my father not only worked for Hughes, he met him. My dad spent over forty years as a ramp serviceman at TWA. When Hughes owned the airline, it offered the last flight to Los Angeles from what was then Idlewild (now Kennedy Airport). Years later, my father told me about seeing pretty much every star from Hollywood’s golden age boarding that plane. More than once, Hughes himself turned up. According to my dad, he’d materialize on the jetway from out of nowhere and say the same thing in his reedy voice: “Got a full bird tonight, boys?” My father would reply, “Yes, Mr. Hughes,” at which point Hughes would nod and vanish again.

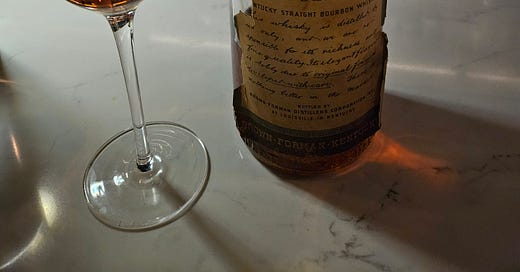

As I reviewed the online spirits list at The Doctor’s Office, my eye was drawn to Hughes’s Old Forester bottled-in-bond bourbon from 1946. It was, as you might expect, something of an extravagance. I’ve always had issues with money, especially when spending it on myself. But the fervor had taken hold of me. I wouldn’t be squandering the equivalent cost of my birthday dinner out with Rosemarie on a single glass of whiskey. I would be buying a taste of the world before I arrived in it. I would be purchasing a brief jaunt back to the heyday of film noir, in the indirect company of a man who had helped bring that era about.

Rosemarie, for what it’s worth, had no use for these arguments. When I told her what I was contemplating, she said, “You need to do this. I’m going to insist that you do it.”

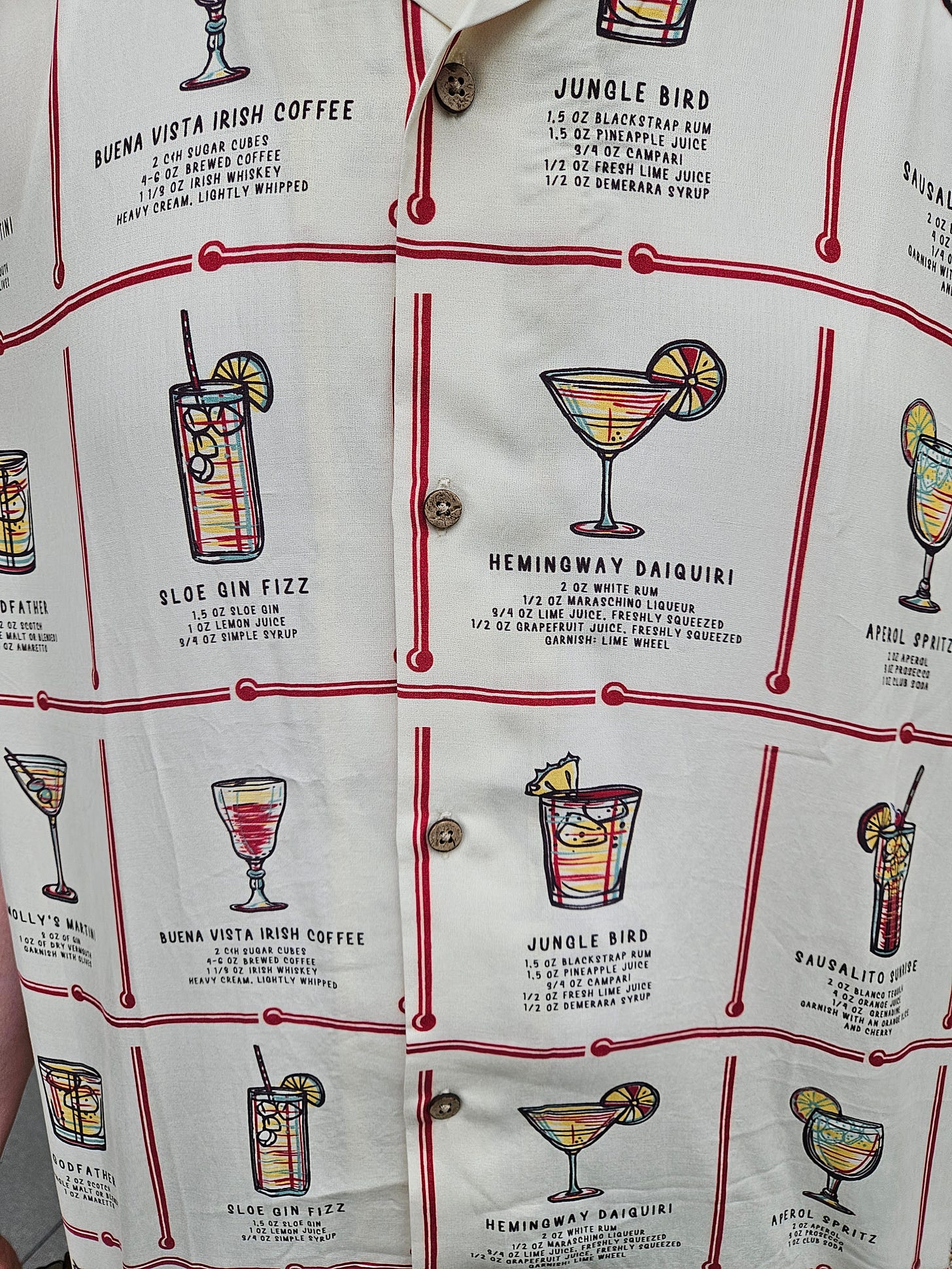

Our appointment arrived. I asked if I should open or close with the Old Forester, and was advised that vintage spirits should always come first, the better to appreciate their flavors. Or as Goldfarb writes, “Hype and history and coulda woulda shouldas can fuck with the palate.” Peter, our bartender, walked us through the Hughes collection, noting that the Minerva gin, imported from Argentina so Hughes could enjoy martinis during the war, packed a lethal burn. Peter hadn’t yet sampled the Old Forester, so he poured himself a small taste and we drank it together.

We both commented on the salinity of the bourbon. I was struck by the potent cinnamon and vanilla notes on the nose, by its long, rounded finish. It wasn’t some exotic ambrosia. It was bourbon, a damned good one. I could have ordered a contemporary whiskey that tasted better at a fraction of the cost. But it was also history, and that’s what I was savoring.

In Dusty Booze, Salvatore Calabrese says, “I always associate the age of the spirit with something happening in the world.” Goldfarb does likewise when, at the end of the book, he visits The Doctor’s Office and works his way through the Hughes collection. For him, the Old Forester calls to mind the workers in Kentucky who made the whiskey before World War II and survived to taste it afterward, along with Hughes’s near-fatal crash of the XF-11 airplane the year the bourbon was bottled, an incident depicted in The Aviator (2004). Me, I thought of movies from 1946, The Killers and The Postman Always Rings Twice and The Strange Love of Martha Ivers. I thought of other films that I’ve watched repeatedly, written about, introduced at Noir City film festivals. I thought of the people who made those films having a drink at the end of the day and reaching for a bottle of this very bourbon. I thought of watching those movies again and this time knowing what that world tasted like, that it smelled of cinnamon and vanilla. Those movies would be more real to me, and even more meaningful.

I nursed that glass of Old Forester for as long as possible, then requested a low-octane prescription to follow it. Peter prepared a Reverse Manhattan with Amaro CioCiaro, Sfumato (made with rhubarb), and Fernet from Mexico. It ranked among the finest cocktails I’ve ever tasted.

Happy birthday to me. This week the Mets are in town to play the Mariners with both teams battling for playoff spots, so the party rolls on.

I don't know if you've been to the revamped TWA terminal at JFK but they recreate Howard Hughes' office. And a cocktail on the Connie is not to be missed.

Happy Birthday!