C&C 39: Sympathy for the Suits

On finally reading FINAL CUT and finally watching HEAVEN’S GATE

I love a bargain and hate a gap in my knowledge, so it’s a red-letter day when the twain meet. As they did when I was browsing one of those desperation racks outside a used bookstore and found an essential Hollywood title that I’d somehow never read priced at only a buck.

Final Cut: Dreams and Disaster in the Making of Heaven’s Gate (1985) is the rarity written from the perspective of a studio executive. When Steven Bach started at United Artists, where he eventually became head of production, novelist and screenwriter William Goldman told him to keep a diary. The resulting book achieves what I had previously thought impossible: it made me feel bad for the people who sign the checks. A little bad, anyway.

Something I love more than a bargain is an anatomy of a trainwreck. Like the calamitous epic at its center, Final Cut opens with a long-winded introduction. Unlike in Heaven’s Gate (1980), there’s a reason for it. Bach chronicles United Artists’ history from its 1919 founding by Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, D.W. Griffith, and Mary Pickford. That pedigree gives UA a reputation as a company that puts filmmakers first, and explains the disconnect in place as Bach ascends the ladder. The studio had been bought by Transamerica, an insurance conglomerate, in 1967. It’s still doing phenomenally well under the decades-long stewardship of Arthur Krim; as Final Cut begins, UA is riding high with two money-making franchises in James Bond and the Pink Panther, and three consecutive Best Picture Oscars for One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Rocky (poised to become franchise #3), and Annie Hall. But there’s tension between Krim’s team and the Transamerica bean counters. UA’s leadership resigns en masse to start Orion Pictures, leaving their successors with a thorny problem. How do you entice talent tastefully? What’s the polite way to flash your bankroll as you stride into the club? Final Cut recounts how Bach and his colleagues ultimately destroyed the company by trying to prove they were still in business.

Their first move, and the one that damned every decision that followed, is to get in bed with Michael Cimino. The buzz surrounding The Deer Hunter (1978) months in advance of its release is deafening, and landing Cimino’s next project will be a bold statement of the new UA regime’s intent. Bach attends an early screening: “The movie was exciting, and it was impressive. It was absorbing, repellent, romantic, touching, brutal, confusing, stirring, annoying, technically sure, structurally shaky, and long.” All of those red flags will wave again. After Cimino’s proposed new version of Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead is shot down—for which we all owe the UA execs a debt of gratitude—the filmmaker offers a western he’d written almost ten years earlier, The Johnson County War. The sprawling, downbeat script has a checkered history, and plays fast and loose with the history that inspired it. UA’s story department declares they’d pass were it not for Cimino’s involvement, and even with it substantial rewrites are needed. Then The Deer Hunter becomes a critical and commercial smash, the deal is made, and the die is cast.

The budget for the rechristened Heaven’s Gate quadrupled to $44 million dollars. Owing to Cimino’s mercurial methods, the production was ten days and fifteen pages behind after only twelve days of shooting; John Hurt, who had signed on to play cowboy as “a lark,” almost had to drop out of The Elephant Man (1980) because of the delays. Bach is not on location often, but when he is the news isn’t good, as when the lead horse wrangler tells him: “Hell, this picture can go on forever as much as I care. My boys and I’ve never been paid like this. I looooove Montana!” As the shoot spins out of control, Bach and his cohorts concoct three possible approaches, each tellingly named for a previous cinematic disaster. There’s the Cleopatra (stand back and let it happen), the Apocalypse Now (try to contain things in hope of minimizing the overages), and the Queen Kelly (pull the plug). Little did they know Heaven’s Gate would enter the language as shorthand for Hollywood excess.

Final Cut features some strained writing, as in this description of UA’s president:

Andy Albeck was not show business; that much was clear. He was the intimate of no great producers; he played poker with no major lawyers; he “tennised” with no powerhouse agents; he supped not with writers or thespians.

But Bach makes up for any awkwardness with candor, readily admitting when he feels out of his depth. He objects to Cimino’s suggestion of the little-known Isabelle Huppert for one of the leads in Heaven’s Gate because “she has a face like a potato,” and is peevish during a Paris meeting with her: “She was tiny, she was lumpish, she made no particular effort to be charming.” (She lands the role, and Bach later calls her “incandescent.”) The best parts of the book detail the complex realities of the studio chief’s job; there’s truly an art to juggling projects and maintaining relationships. Woody Allen plays a vital supporting role, as the four-picture deal he signed during the Krim era comes to a close and Bach labors to keep him in the UA fold. That pact yielded Annie Hall and Interiors (1978), Bach noting that the latter “may be one of the rare instances in modern American movie history in which an artist has been allowed to make a picture because of what it might mean to his creative development, success or failure.” It also included Manhattan (1979), which Bach says provided “two hours in my three years and three days at United Artists that remain in memory as pure, unambiguous pleasure.” It’s a peak-era Allen movie that I haven’t revisited because it struck me on first viewing as skeevy. Now I’d find it impossible to sit through. Bach professes indignation that the film received an R rating not due to language but because it’s partly about a 42-year-old man having a romantic and sexual relationship with a 17-year-old girl.

The book gains in power as the Heaven’s Gate debacle threatens the company, and Bach’s prose improves. A sharp sequence depicts the delicate dance between art and commerce as Bach and exec David Field try to convince Martin Scorsese and Robert DeNiro to make Raging Bull (1980) more palatable, with DeNiro revising much of the screenplay. A vignette about Peter Sellers writing an abortive Pink Panther sequel captures the actor’s idiosyncrasies. And there’s a vivid sketch of the grim Heaven’s Gate premiere, where guests refuse the complimentary intermission champagne because they hate the movie that much. The book ends with MGM buying the weakened UA for its distribution arm so it can release as dire a slate of movies as has ever been assembled, courtesy of the disgraced David Begelman, including Buddy Buddy and Yes, Giorgio.

As I finished the autopsy of Heaven’s Gate, I thought: I’m gonna have to watch this fucking thing, aren’t I? The film has been reassessed since 1980, earning its adherents. Maybe I’ll be one of them. I’ll mount a grudging defense, saying I found much to admire amid its extravagance.

Nope. Sorry to disappoint; perhaps there are other Substacks that may be more to your liking. The UA story department had it right. Heaven’s Gate, even in Cimino’s preferred cut, is a bad business decision and a brutal slog. I made it through all 218 minutes out of pure orneriness.

Which is unfortunate, given that its core story about the clash between cattle barons and immigrants has renewed relevance. An exchange between Jeff Bridges’s Bridges (playing an ancestor who lived in Wyoming at the time) and Kris Kristofferson’s nominal hero James Averill still stings.

Bridges: It’s getting dangerous to be poor in this country, isn’t it?

Averill: It always was.

As does this line delivered by Richard Masur’s Cully: “If the rich could hire others to do their dying for them, the poor could make a wonderful living.” I hope you enjoyed that dialogue, because the rest of it is repetitive, didactic, obscure, or some combination of the three. Cimino’s script fuses the poorly dramatized political story with a thin love triangle in which Huppert must choose between Kristofferson’s Averill, a cipher, and Christopher Walken’s Nate Champion, a bastard. The first face-to-face sober confrontation between the two suitors occurs at the film’s halfway mark, a point at which many of the finest westerns ever made—Stagecoach (1939, 96 minutes), Winchester ’73 (1950, 93 minutes), High Noon (1952, 85 minutes)—have already tended to business and allowed audiences to mosey on home.

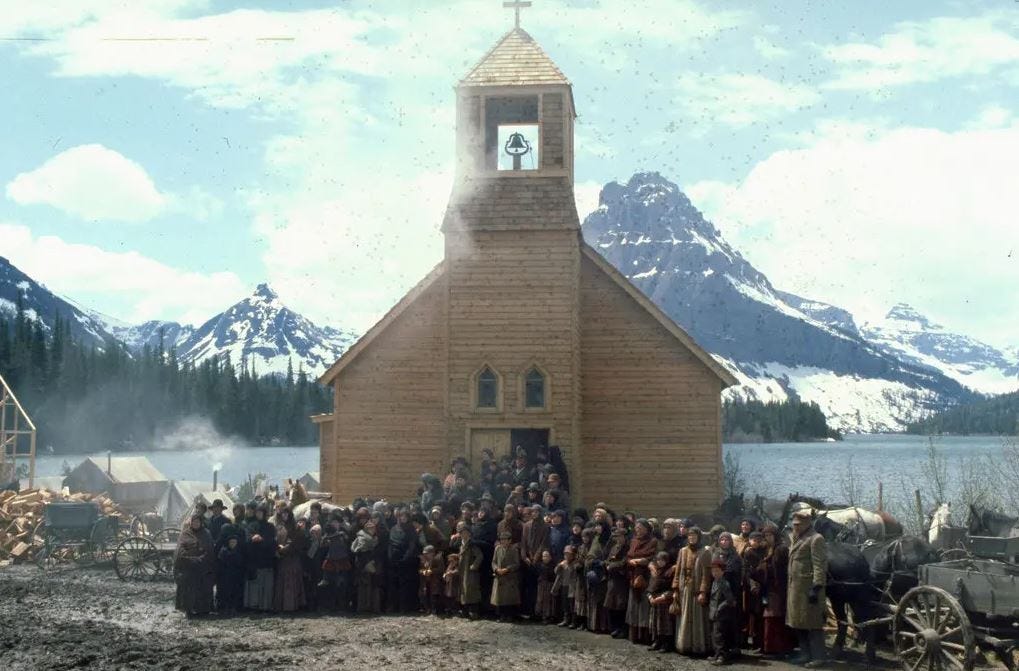

A constant refrain in Final Cut is that the footage looks “as if David Lean directed a western.” (When UA contemplates firing Cimino from his own film, Lean—whose planned two-part version of Mutiny on the Bounty for the studio collapses during this same period—is one of the few replacements they consider.) Heaven’s Gate is unquestionably gorgeous. One breathtaking shot follows another. The whirl of hundreds of dancers waltzing around a tree to “The Blue Danube” after a Harvard commencement ceremony. The scrum in the streets of Casper, Wyoming, a city being erected seemingly in real time hard against the mountains. A train full of hired killers idling before a snow-capped peak. The movie is a procession of screen savers that ends in a bloodbath. That climactic donnybrook is stripped of all logic, neither the assault nor the defense making any sense. Cimino, understandably besotted with his visuals, holds every shot and scene too long. He creates elaborate set pieces of no consequence, like the famed hoedown featuring more roller skaters than the ending of Xanadu (1980)—but somehow not Christopher Walken. If anybody in this movie should be dancing on wheels, it’s Walken. When the credits mercifully rolled, I felt as if I’d spent three and a half hours with people waltzing, skating, riding, and talking in circles.

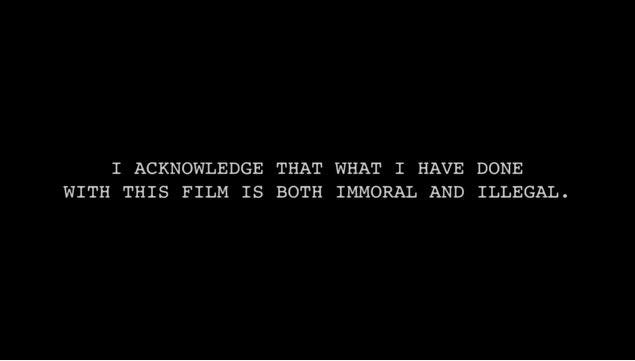

Steven Soderbergh, under his editing nom de plume Mary Ann Bernard, released his “butcher’s cut” of the movie, slashing the running time in half. He wrote, “unfortunately history has shown that on occasion a fan can become so obsessed they turn violent toward the object of their obsession, which is what happened to me during the holiday break of 2006.” As a Soderbergh superfan, I am sorely tempted to watch this version. But I’ve dedicated enough time to Heaven’s Gate. If you’ve read this far, so have you.

Great stuff, VK! I agree, I watched the Cimino cut out of mere curiosity, an absolute slog as you described it and a mess. I saw YEAR OF THE DRAGON the day it came out in the theater and was disappointed in it. Last year I rewatched it to see if I felt differently… no, that film is a mess too.

Great write up. I feel pretty much as you do about the film--watching Once Upon a Time in the West, the grandeur always feels in service of some story point or emotion, whereas with Heavens Gate seems like they built an entire town and didn't know where to place the cameras or what story to tell.

I rewatched Thunderbolt and Lightfoot recently and really liked that one. But Heavens Gate is a mess.