Throughout high school and college, I worked as an usher at movie theaters. The job allowed me to see films for free, and considering that’s what I spent most of my money on, it was like doubling my meager salary. I could pick up shifts all summer and during the holidays when I went home.

That job is how this situation happened, and why the circumstances remain somewhat hazy.

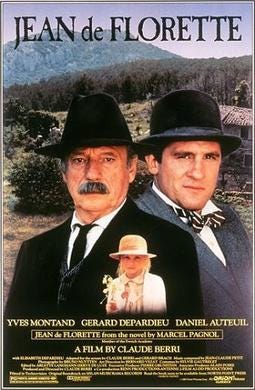

One of the foreign film hits of 1987 was Jean de Florette, Claude Berri’s adaptation of a novel by Marcel Pagnol. (Pagnol initially told the story on film in 1952, writing the book only after the distributor slashed the movie’s four-hour running time in half.) I saw Berri’s film in its entirety at least three times, and when it played at the theater where I was working I’d slip into the back to watch certain scenes over and over. This is the kind of thing I did a lot. I can still perform a number of minor movies from the late 1980s in their entirety.

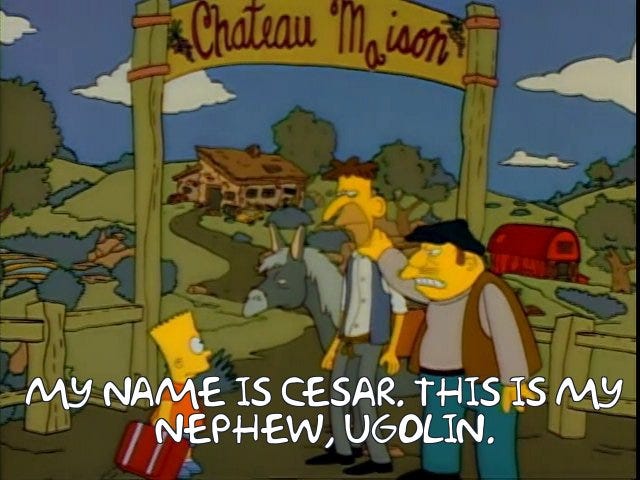

In Berri’s film, César, a wealthy Provencal landowner played by Yves Montand, welcomes his nephew Ugolin (Daniel Auteuil) home from military service. He supports Ugolin’s dream of cultivating carnations and even knows the perfect plot of land for the profitable endeavor, one that boasts a secret spring. But when César tries to purchase the property from its contentious owner, they quarrel and César accidentally kills him. He decides to buy the land on the cheap from the relative who stands to inherit. To seal the deal, he and Ugolin plug the spring with cement. But Jean Cadoret (Gérard Depardieu) arrives with his family in tow and his head full of modern ideas. The big-city tax collector, born a hunchback, has every intention of living out his days on the land. Ugolin, at César’s direction, becomes Jean’s friend and confidant, secretly undermining his plans. Ugolin becomes conflicted as, in the face of hardship, Jean grows more determined to realize his vision. It all builds to a satisfying, almost Biblical denouement.

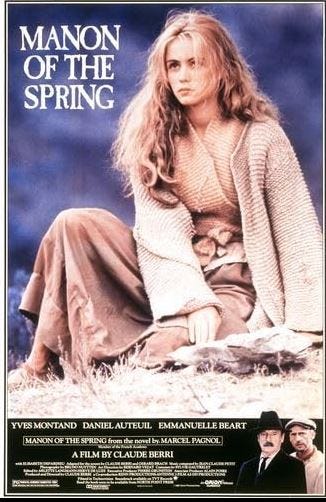

Jean de Florette then closes with the words End of Part One. The rest of the story is told in Manon of the Spring, released later that year.

Only I never saw it.

Manon opened over the holidays in 1987. As near as I can figure, somewhere between college in Boston and home in South Florida, where my family was living at the time, I missed it.

Could I have caught up with it? Of course, although digging into the practical reasons why I didn’t is like explaining how switchboards operated or that cigarette machines used to be commonplace. Foreign language films seldom turned up on cable TV, and your average video store didn’t carry many of them. I’d occasionally find a copy on a shelf and tell myself that an opportunity to see it on the big screen would come along one of these years. Or decades.

I was thrilled when a reference to the movies cropped up in a season 1 episode of The Simpsons in 1990. It was an obscure joke at the time. I have to be one of the few who get it now.

Jean de Florette continued to haunt me. I’d wonder what became of the characters, but I never looked up the answer. An image of Depardieu, weighted down with jugs of precious water as he leads a similarly-laden mule along a treacherously narrow track, would pop into my head unbidden. I could still hear the theme music, adapted from Giuseppe Verdi’s opera La Forza del Destino, in particular Jean’s harmonica rendition performed by the incomparable Toots Thielemans.

Still, I didn’t watch Manon of the Spring. And the twentieth century became the twenty-first.

Last year, the Criterion Channel acquired 4K restorations of both films. Great, I thought, now is finally the time.

And still I didn’t watch Manon of the Spring. And now it gets harder to explain.

On some level, I supposed it made for a fun fact, not that I ever had cause to drop it into conversation. What’s more likely is I was subconsciously saving the movie for my dotage, a delayed gift for my twilight years. And I’m nowhere near those yet, right?

Rosemarie recently read Adam Bede by George Eliot. In describing the book, she used the word rustics. And that pushed me over the edge. That night, I dreamed about Jean de Florette. Not the first time that’s happened. In the morning, I asked Rosemarie if she wanted to spend the weekend watching both films. She’d never seen either one.

What changed? I’ve reached an age where it’s time to start closing doors instead of leaving them ajar. There are enough stories in life to which I’ll never know the endings; some of them I’m a part of. With this one, at least, I could sate my curiosity. Besides, I know myself. There’s every possibility I’d never get around to Manon of the Spring, and that failing would be one of my final thoughts on my deathbed.

First, Jean de Florette. The restoration is a marvel; Provence has never looked so beguiling. On this viewing, I was struck by how it prefigured Killers of the Flower Moon. A rich man manipulates a simple-minded relative into a deceptive relationship with a third party in order to reap the benefits of that party’s land.

In any longstanding marriage, you still want your partner to look at you every once in a while as if seeing you for the first time. Rosemarie fixed me with such a gaze when Jean de Florette ended. “You went HOW LONG without seeing the other half of this?”

I shrugged. No explanation made sense anymore.

We watched Manon of the Spring the following evening, after spending the day convinced that some bizarre accident would befall me, thwarting my best intentions at the last moment. Didn’t happen.

Manon of the Spring takes place ten years after the events of Jean de Florette, with Jean’s daughter Manon (now played by Emmanuelle Béart) a spectral shepherdess in the hills beyond what had been her family home, hoping to seek revenge. She’ll find a way to do so that implicates the entire town. The character is too winsome, robbing her vengeance of some of its power. But Manon is ultimately Montand’s film. His aging César has become embittered as only the wealthy can, furious that the money and influence they have amassed will not spare them the grave. Worse, he fears he will be held to account for his misdeeds before he dies, tarnishing his legacy. The film serves as a devastating example of Aristotle’s counsel that endings should be surprising but inevitable. In almost forty years, this particular turn of events somehow had never occurred to me despite its being meticulously set up. More importantly, it felt like a finale worth the wait, a fitting conclusion to a small but significant chapter of my own life.

And it’s a reminder that I should see Dune: Part Two before it closes.

What I’m Drinking

I wanted a cocktail with a French vibe to toast Manon of the Spring, and couldn’t think of a better one than the Ce Soir. Created by bartender Nicole Lebedevitch at the Boston bar The Hawthorne and popularized by Robert Simonson, this elegant libation complements its cognac base with the artichoke-flavored amaro Cynar—a huge favorite—and yellow chartreuse, along with what Lebedevitch described as “the salt and pepper of the combination of the Angostura and Regan’s orange bitters.” Très formidable.

Ce Soir

2 oz. cognac (Lebedevitch recommends Pierre Ferrand 1840 Original Formula)

¾ oz. Cynar

½ oz. yellow chartreuse

1 dash Angostura bitters

1 dash Regans’ No. 6 orange bitters

Stir. Strain. Express a lemon twist over the drink.

These are both on the Criterion channel... thanks, my weekend is now sorted!

What a great essay!