C&C 35: From Albee to Zwick

A pair of worthwhile new books about show business

If you asked me to list Academy Award-winning filmmakers who have been directing studio features for four decades, it might be a while before the name Edward Zwick occurred to me. That stealth longevity is even more impressive considering that he simultaneously maintained a noteworthy track record in television (thirtysomething, My So-Called Life). He’s made several movies that I like, some I haven’t seen, and one I absolutely hate. (Don’t ask, I won’t tell you.) That résumé certainly qualifies him to write a Hollywood memoir. The candor on display in Hits, Flops, and Other Illusions (2024) makes it essential reading.

Zwick regularly calls out his failings and excesses. Sometimes his honesty seems unintentional. There are a few too many stories like the one he tells about writing The Siege (1998)—one of his best films, with a scene involving cell phones at a briefing that still gives me chills—and starting his research by calling Merrick Garland, currently the US attorney general and then a deputy AG, whom Zwick “had first met at a tea for Chicago high school students entering Harvard College in the fall of 1970.”

He’s forthright about difficulties he’s encountered with collaborators, always in a compassionate way. The chapter about Shakespeare in Love (1998) is revelatory. Zwick spent years developing the script, eventually bringing in playwright Tom Stoppard, whose revisions enticed Julia Roberts to play the lead role. Zwick recounts how Roberts, then in the frenzied full bloom of her Pretty Woman stardom, couldn’t settle on a costar, torpedoing the film. (His stories about Harvey Weinstein, who seized a producing credit when the project was revived at Miramax, are nowhere near as empathetic.) Astoundingly, Zwick would yield the director’s chair on Traffic (2000), a second Oscar-nominated film to which he’d devoted substantial time, and writes about these high-level experiences with a perspective few can offer. Late in the book he reels off a list of projects with big-name collaborators that never came to fruition, because decades in show business mean a lifetime of disappointments. Every movie that gets made, even the ones that tank, is a miracle, and Zwick treats them as such.

He wonders if, as a white man, he’d be able to make the Civil War drama Glory (1989) now; laments being told by a studio chief after the lackluster box office for Blood Diamond (2006) that the film, “a big movie just for adults,” is “the last one of its kind we’ll ever make;” confesses that he observes “the talented young directors coming up with admiration tinged with a certain wariness” because their films “seem not at all interested in holding up a mirror to contemporary life;” and openly addresses what it feels like as an artist “after the caravan has moved on.”

I want three things from such books: gossip (check), hard truths (check), and advice. On the last score, Zwick continues to dole out the good stuff. The one that will stay with me comes when Zwick defends the “cool plot” of a script he’s written to his mentor.

“Listen, kid,” he said. “Plot is the rotting meat the burglar throws to the dogs so he can climb over the fence and get the jewels, which are the characters.”

Now that is a vivid metaphor. That the image comes from the urbane Sydney Pollack makes it resonate all the more. I thought of Pollack’s counsel when I read Laura Lippman’s observation in her latest newsletter that most of the current Best Picture nominees “had no idea after THE idea,” and that genre writers must be wary of this pitfall because “there are plenty of readers who will be happy if we just execute the plot mechanisms of our story.” Other pearls of eminently practical wisdom from Zwick:

Coverage is God’s way of giving you the chance to rewrite in the cutting room.

When in doubt, take a nap.

I nodded. Another important part of directing is nodding.

After fifty years of getting their notes, the sum creative contribution from all but a few truly gifted executives might be reduced to four words: “Faster. Dumber. More likeable.”

Professionals do some things they love because they love them, and some they don’t love, or even like. But they do them all as if they love them.

Early on, Zwick professes his admiration for William Goldman’s Adventures in the Screen Trade, source of the oft-quoted Tinseltown dictum “Nobody knows anything.” I scoffed, knowing that no memoir could compare to it. But Hits, Flops, and Other Illusions comes a lot closer than I thought. Another stealth victory in a career full of them.

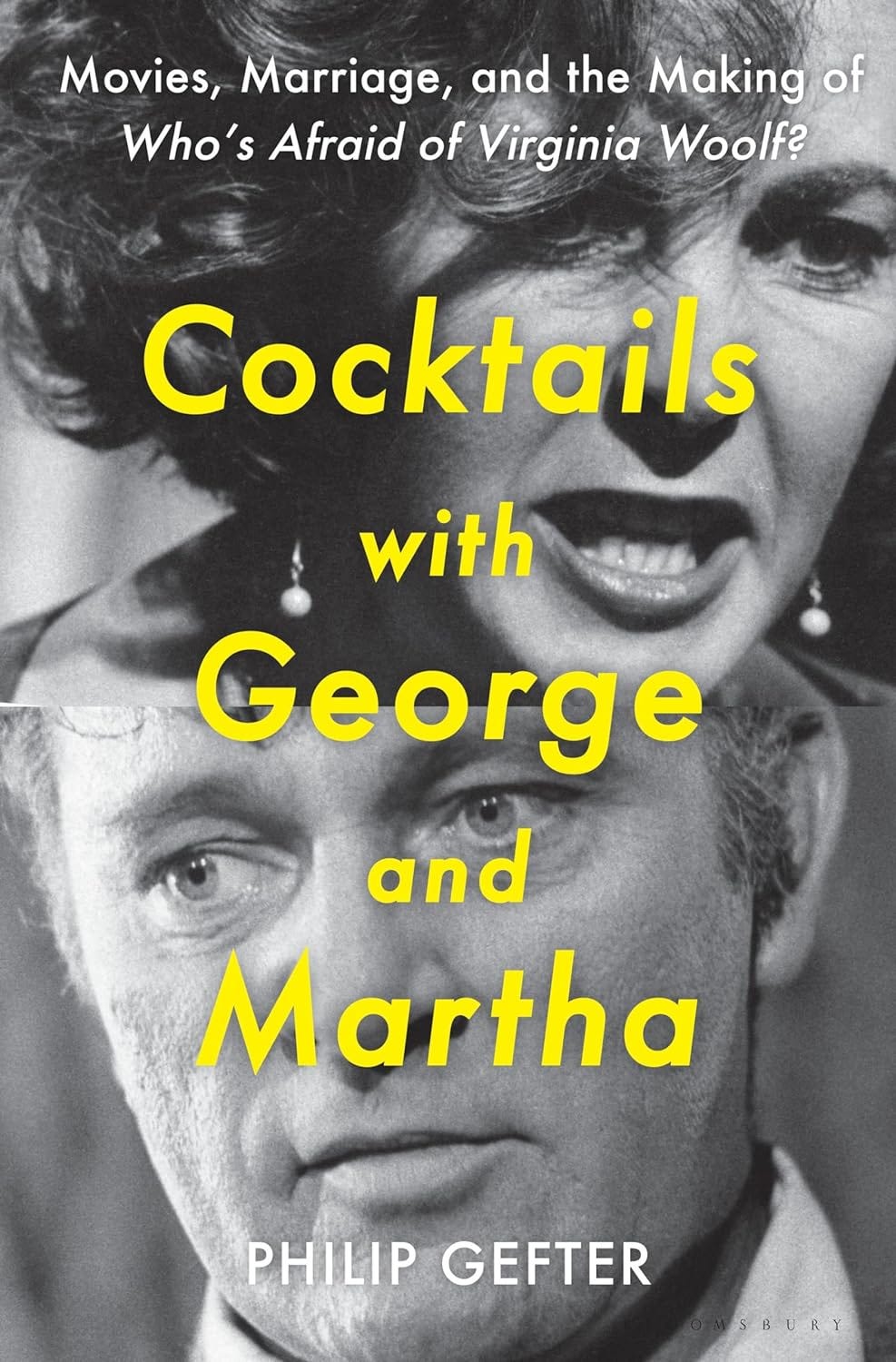

In Cocktails with George and Martha (2024), Philip Gefter considers Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? in all its forms: Edward Albee’s 1962 play, the 1966 film adaptation directed by Mike Nichols, and a story not about a single marriage but the institution in general. The focus understandably favors the movie, owing to its storied and complicated production, with Nichols making his debut behind the camera and the tumultuous union of Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton in front of it, mirroring and in some ways augmenting the play’s themes. Gefter does ably sketch Albee’s life and the dizzying ferment of New York City in the late 1950s and early 1960s. He also captures the play’s galvanizing impact. If Cocktails can be said to have a hero, it’s Ernest Lehman, the veteran screenwriter acting as producer for the first time. Lehman is described in Laurence Leamer’s recent book Hitchcock’s Blondes (2023) as “a quiet man with all the charisma of a toll booth operator,” but here he emerges as a compelling bridge between the new sensibility of Nichols and many of his collaborators and the old guard represented by studio boss Jack Warner—and, to an extent, Lehman himself; he’d just written The Sound of Music, after all. Lehman also makes a fantastic guide through the arcane art of Hollywood gift-giving. The closing chapter considering the many works that mine the terrain mapped by Albee’s groundbreaking work, from Ingmar Bergman’s Scenes from a Marriage (tellingly, Bergman directed the play’s European premiere) to Noah Baumbach’s Marriage Story, is somewhat scattered, but on the whole the book is a compelling work of cultural history.

What I’m Watching

@fter midnight (CBS). Best thing about the expanded reboot of this comedy game show: the preternatural ease with which standup comic Taylor Tomlinson asserts her hosting chops. (Her new Netflix special Have It All is also definitely worth watching.) With Tomlinson and a panel of three comedian contestants, it’s the loosest show on TV. It also functions as a controlled dose of TikTok, so I never have to join the platform. Like, ever.

I have both these books on hold at the library. I look forward to reading them especially the book about Virginia Woolf. I've always thought that Elizabeth Taylor rose to the occasion when she was given the material.